The above named report by the ILO and UNESCO Education Sector[i] asks the highly pertinent question, “Does the adoption of inter-ministerial coordination mechanisms assist in the achievement of TVET and skills development policy objectives?”

Why is it Important?

In a rush to mass skill populations to avert crises of unemployment, governments often find themselves scrambling to put too many wheels into action with little coordination. When things start to fall off the bandwagon the very purpose of skilling programmes suffers from the incoherence in TVET systems.

A heavily skewed focus on implementation of TVET policies and schemes often sees measuring of outcomes, effectiveness of training, monitoring and evaluation fall off the grid. Ergo, we find this report eminently relevant as it goes beyond the usual narratives and asks how inter- ministerial coordination affects policy outcomes? We feel this is extremely germane to the Indian context as we find ourselves at the crossroads of high youth unemployment, low employability and not enough good jobs and; much of it owing to lack of industry relevant skills.

The report elucidates the main functions of TVET governance:[ii]

As we have seen, skill development has received a massive fillip in recent years with the introduction of schemes such as the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme– with a corpus of Rs 10,000-crore[iii]. The government’s hankering for 50 lakh apprentices by 2022 albeit well intended, will depend heavily on actual outcome which means equally prioritising programme implementation and evaluation along with policy development. In other words, ‘getting things done’, or in World Bank parlance ‘the science and politics of delivery’.[iv]

Critical Success Factors in Inter-Ministerial Coordination

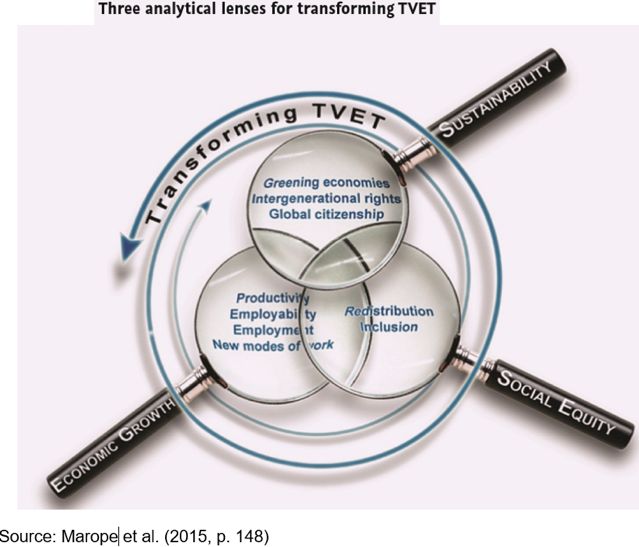

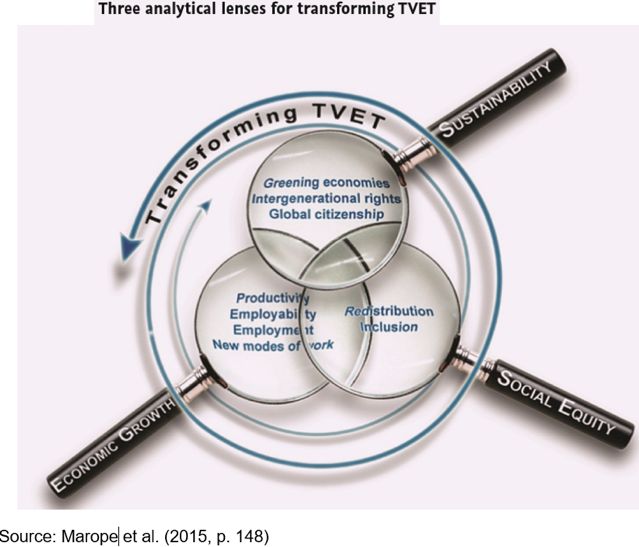

Here, the three interlocking ‘analytical lenses’ of economic growth, social equity and sustainability form the basis for defining ‘success’ of a country’s TVET governance.[v] Not achieving any of these demand areas points to a major disconnect between ‘the analysis of TVET systems with intended development outcomes’. [v]

The ‘three lenses’ provide a flexible framework for governments to assess the strength of their TVET governance by changing the weighting of each depending on local and political priorities. In the Indian context we could say ‘economic growth’ becomes weightier with unemployment being a major issue. Or ‘social equity’ comes into focus to skill the country’s vast unorganised workforce.

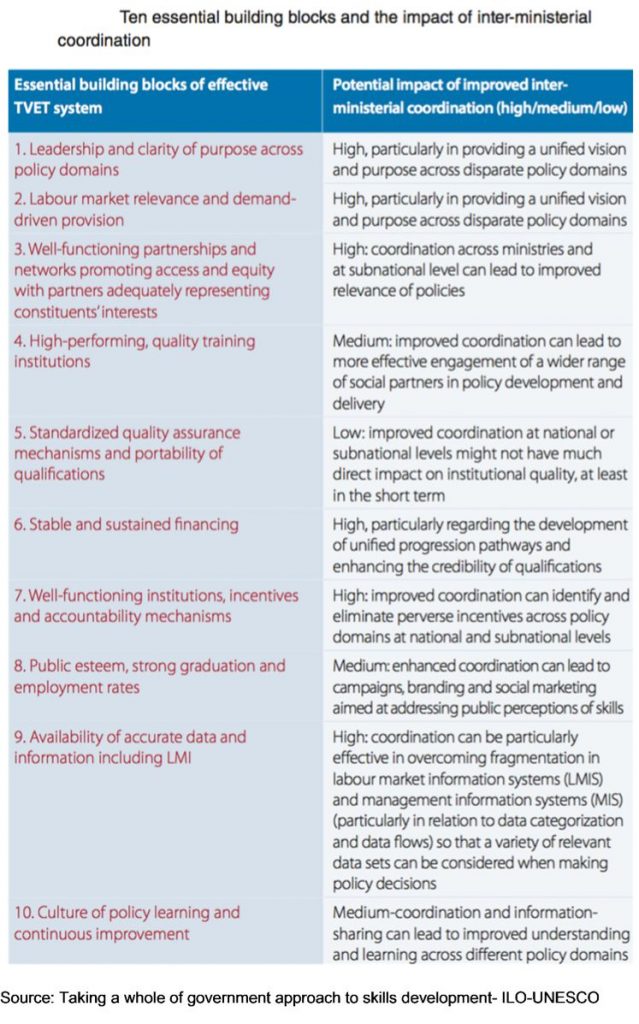

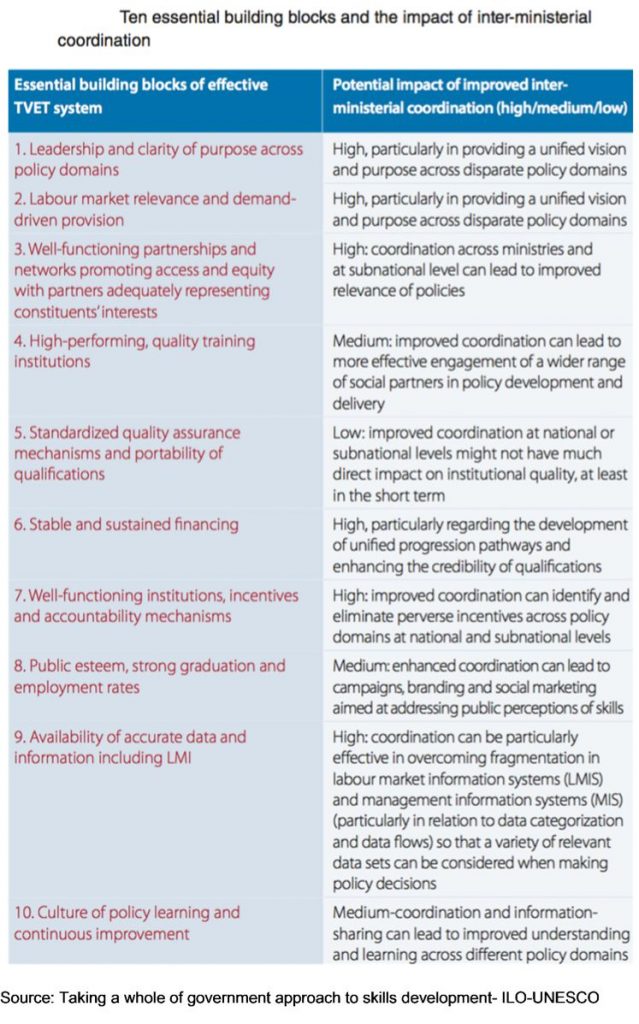

Which brings us to the question what are the key foundational requirements in TVET governance to achieve successful outcomes in the context of the three lenses? And how critical is inter-ministerial coordination to achieving TVET policy objectives? The answers lie in the ten essential building blocks of an effective TVET system which the report’s authors have developed to gauge the impact of inter-ministerial coordination on each block.

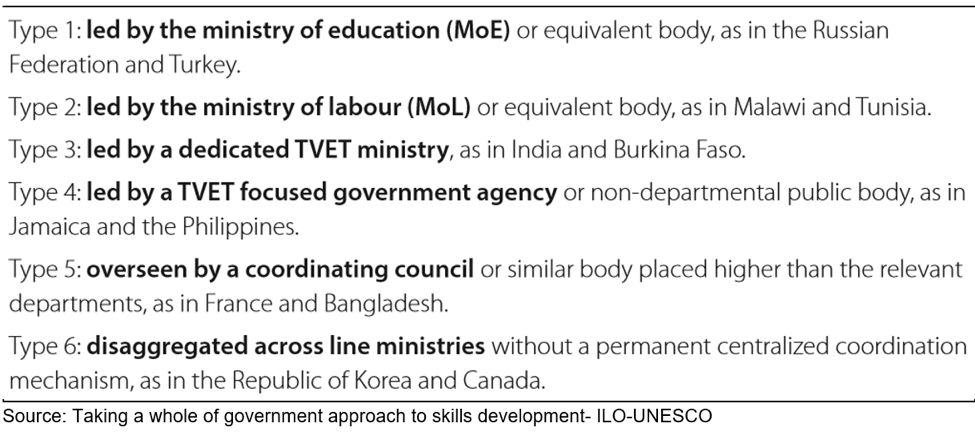

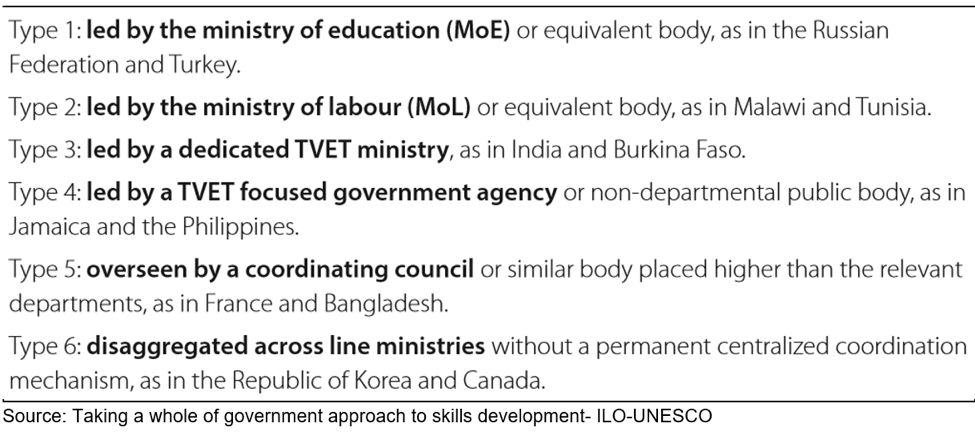

Of course, TVET systems vary across countries and to understand how the essential building blocks play out among the variances the report looked at six broad models of TVET and skill development government systems:

Is One Better Than the Other?

No, states the report’s analysis. Neither of the six TVET governance styles is consistently able to outperform the others across the ten building blocks. It is the presence of foundational features that ultimately impact the quality of governance and how effective inter-ministerial coordination is:

- Authority of the TVET governing body over policy implementation and funding

- Distinct roles and responsibilities of myriad stakeholders

- Continuously scanning and changing (if required) mechanisms for inter-ministerial coordination

- TVET integration with a larger HRD strategy

- Back-up resources and coordination measures to deal with unforeseen situations

- Linkages with industry and response time to labour market changes

What Else?

Whatever type of TVET governance system, some of the building blocks are harder to introduce and maintain than others which is to say the type of TVET governance in a country is not the sole determinant of its success.

In particular, the report emphasises real outcome as a true reflection of how well coordinated the national system is with sub-national and local levels. We fully agree. With some 18 different ministries overseeing skills training in India[vi]– and ruefully little synchronisation between them, the quality of coordination between national, regional and local levels of TVET governance is fraught with inefficiencies. Efficacious coordination between these various levels becomes even more critical in the context of decentralisation and devolution of authority- i.e. shifting more power to local hands in skill development schemes. A well-oiled TVET governance machinery at all levels spawns the responsible utilisation of resources and the risks of overlapping and contradictory interventions are greatly reduced.

Next up

Trigger Points that can facilitate or hamper inter-ministerial coordination efforts.

References

[i] Main Source: Taking a whole of government approach to skills development (2018)- ILO-UNESCO Education Sector

[ii] Cross-Country Report on VET Governance in the SEMED Region- Leney, T. 2014

[iii] Centre to unveil mega apprenticeship programme for undergraduates- Dec 18, 2018 Moneycontrol

[iv] Delivery units: can they catalyse sustained improvements in education service delivery? Paper presented at Australasian Aid and International Development Policy Workshop, Australian National University, 14 February, Todd et al., 2014

[v] Unleashing the Potential: Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Paris, UNESCO- Marope et al., 2015

[vi] India’s skilling challenge: Lessons from UK, Germany’s vocational training models, June 4, 2018, Observer Research Foundation