Read Parts I, II and III for a sequential appraisal of inter-related themes of this ILO report.

In this concluding section of our series on the above named ILO report[i], we examine the remaining two activity themes of employer and worker group participation in apprenticeships. Representatives of the two groups from India in this report are the All India Organisation of Employers (AIOE) and the Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS).

Part III has the first two themes.

Theme 3: Roles and responsibilities

Why should employer and worker groups have adequate sway over the design and operational considerations of apprenticeship systems? These groups are privy to valuable insight from interacting with their members, and can lend a very distinct angle on how apprenticeships can be leveraged for skill building from the perspectives of employers and workers.

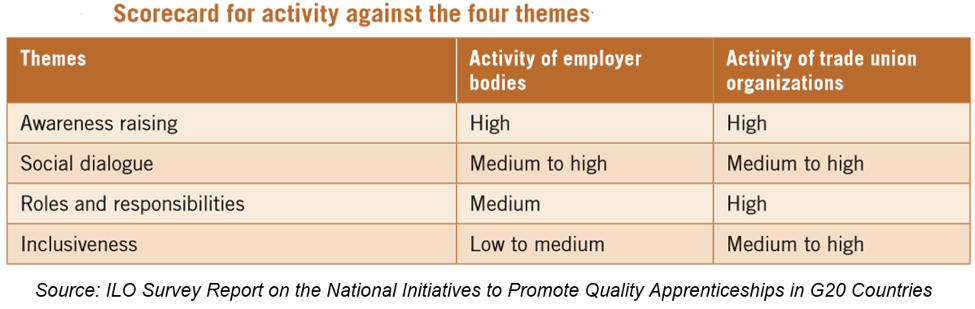

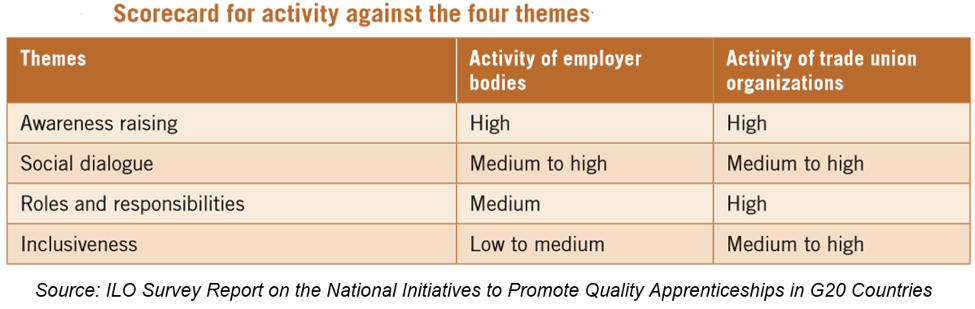

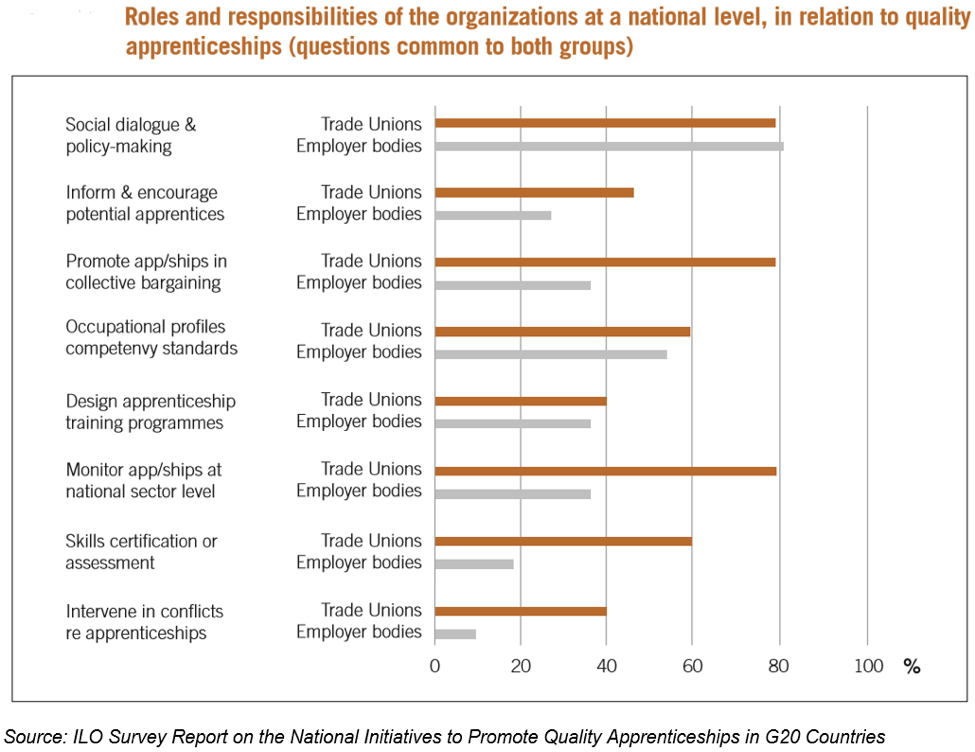

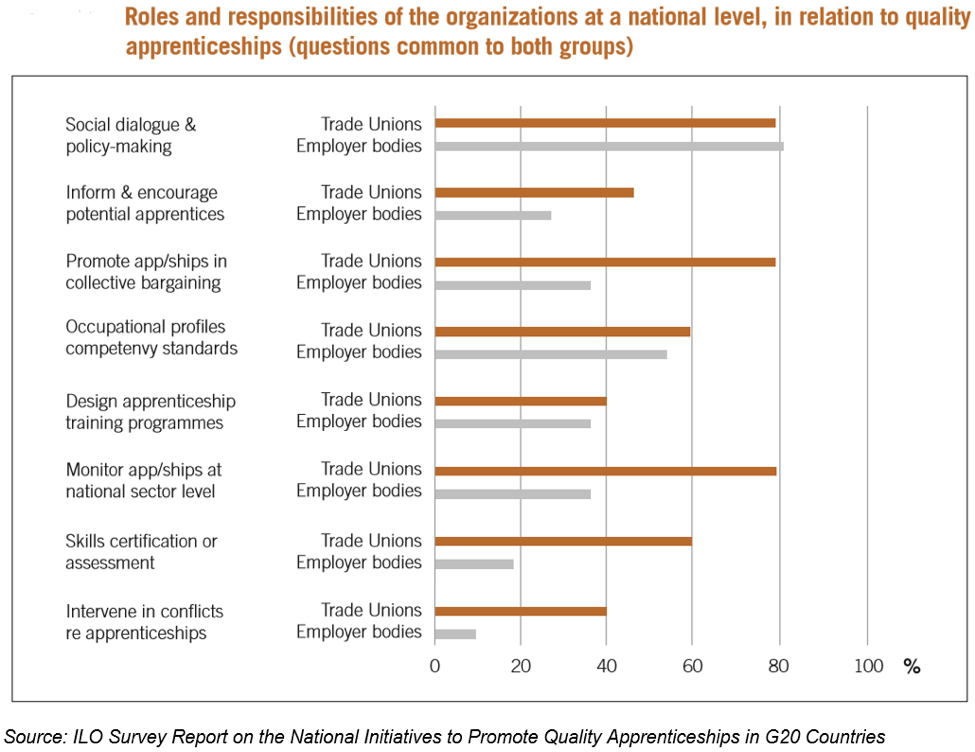

Across the different functions, trade unions were found to be much more actively involved, except in social dialogue and policy making where employer bodies were almost equal participants.

Trade unions made notably greater strides in monitoring of apprenticeships on a national scale, using collective bargaining to promote apprenticeships, conflict management in worker rights, and interestingly, far more visible participation in assessing and certifying skills than employer groups.

The reasons for correspondingly low involvement of employer groups are beyond the scope of this survey. We know that apprenticeship systems vary across countries owing to individual socio-economic and political circumstances, hence there could be many possibilities for differing participation rates of stakeholder groups.

Overall, both the AIOE and the HMS from India gave very little input on their roles and responsibilities at a national level around apprenticeships. The AIOE responded in a general way about organizing training workshops as a targeted initiative to encourage its members to promote apprenticeship training. As we have seen, of late, efforts have been drummed up to encourage industry in all matters of apprenticeships, such as to take advantage of the various offerings and pecuniary support under the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS). For instance, Indian Leadership Council members last year pledged to become brand ambassadors of the NAPS.[ii]

In a similar vein, at a recent NETAP-IAF event on ‘Leveraging the Power of Apprenticeships for Creating Human Capital’, Joint Secretary MSDE, Rajesh Aggarwal, gave a clarion call to the industry. “One of the key things the government tried to change was to remove the critique that curricula and courses designed by government or government regulated entities are not in sync with industry and to give industry the lead to define competencies that they require for the future workforce, and for industry to design curriculum, train, assess and certify,” he said.

Theme 4: Inclusiveness

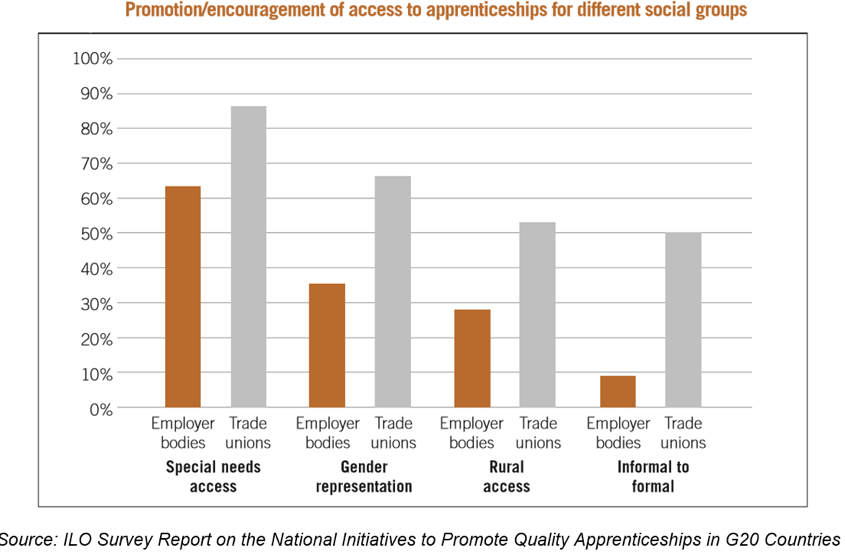

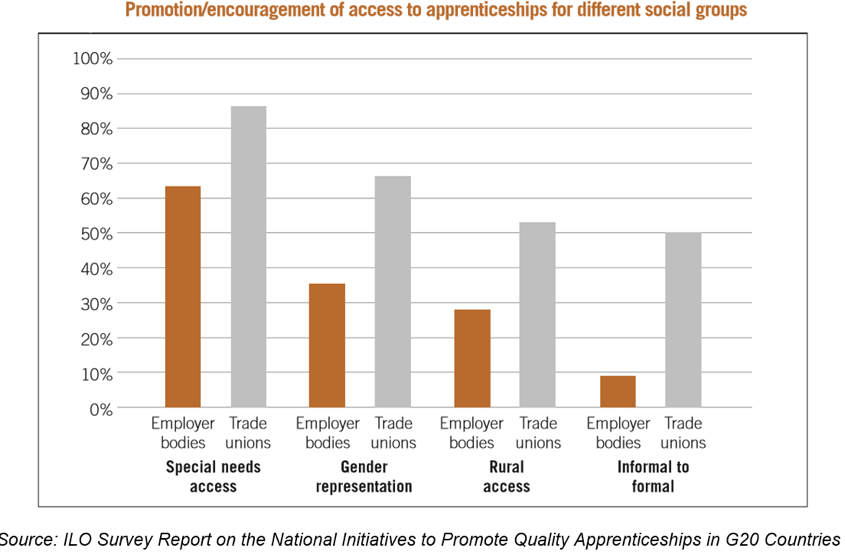

Some groups are more socially and economically challenged than others in finding meaningful employment; such as special needs individuals, women in certain cases, the rural populace, and others from backward sections of society. What role can employer and worker groups play to promote inclusiveness in apprenticeships? The survey responses were high for special needs groups, moderate for gender representation, and registered least activity in providing access to apprenticeships for rural people. Again, across inclusiveness functions, trade unions were more involved, in fact, twice as active around gender and rural issues.

The Indian trade union HMS reported access to special needs groups to be a key feature of their negotiations with employers. However, neither the HMS nor the AIOE answered the question on taking action in the three years prior to this survey to improve access to quality apprenticeships for the rural populace or to transition informal apprenticeships into formal ones. With 90% of India’s employment in the agricultural sector informal, and approximately 70% in other sectors,[iii] a lot more gusto and visible contribution is needed from all stakeholders to leverage apprenticeships to lower the informality malaise in the country’s workforce.

Only the HMS responded ‘yes’ to the question on being involved in improving gender representation in apprenticeships although no specific initiative was stated. As we have noted, only 28.5% of women were part of the Indian workforce in 2017.iv And, India could potentially see a 16-60% GDP growth by 2025 provided women are given equal employment opportunities.[iv] A lot more can be done to make apprenticeships equal opportunity providers to bridge this gap.

Conclusion

This ILO report published in 2018 underscores one of the fundamental premises of robust and mature apprenticeship systems- the criticality of a participatory framework where all stakeholders have an equal voice. We hope the recent trends and developments captured by the report pique the interest of decision-makers in India’s apprenticeship ecosystem to strengthen linkages between relevant partners to make apprenticeships truly effective as a pathway to skilling.

References

[i] Main source- ILO Survey Report on the National Initiatives to Promote Quality Apprenticeships in G20 Countries, ILO- JPMorgan Chase Foundation, 2018

[ii] Skills Ministry banks on India Inc to help in apprenticeship, Oct 7 2018, Economic Times

[iii] National Sample Survey Office, Informal Sector and Conditions of Employment, NSS 68th Round, (2011-2012), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

[iv] World Economic Forum, The Global Gender Gap Report 2017