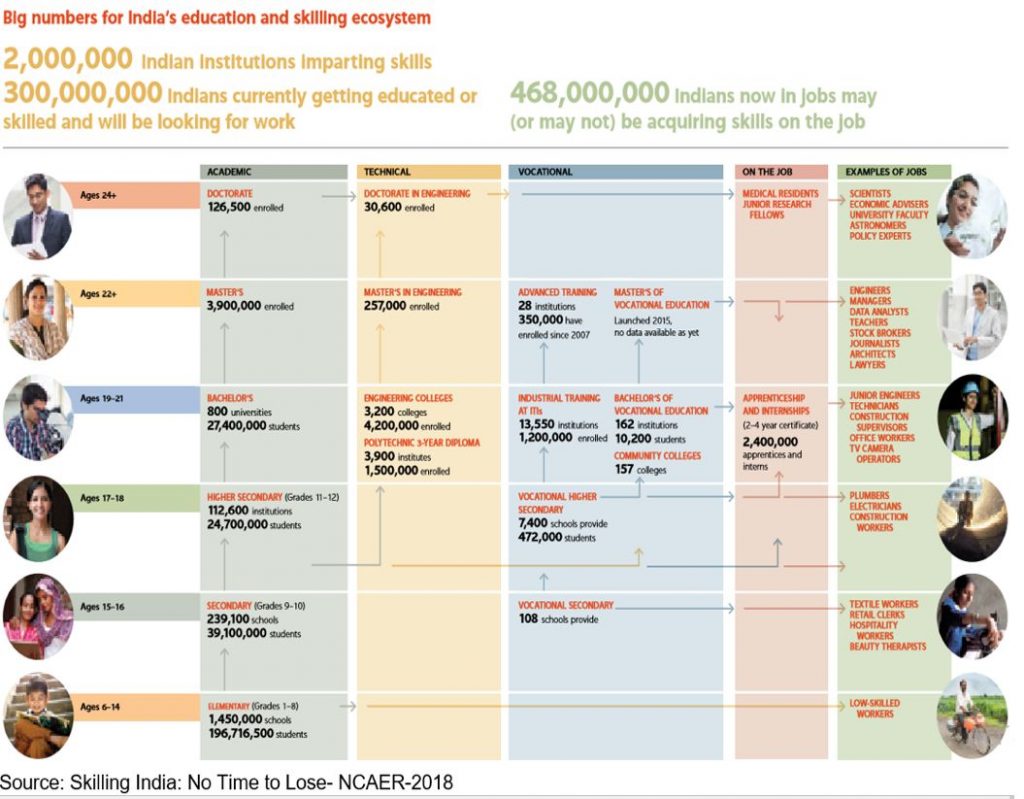

Acquiring & Imparting skills– requiring an overhaul in K-12 education, vocational and technical education and on-the-job training- is part of a three-component framework which the Skilling India: No Time to Lose- NCAER 2018[i] report proposes to boost the effectiveness of skilling in India.

Read the introduction to the report here.

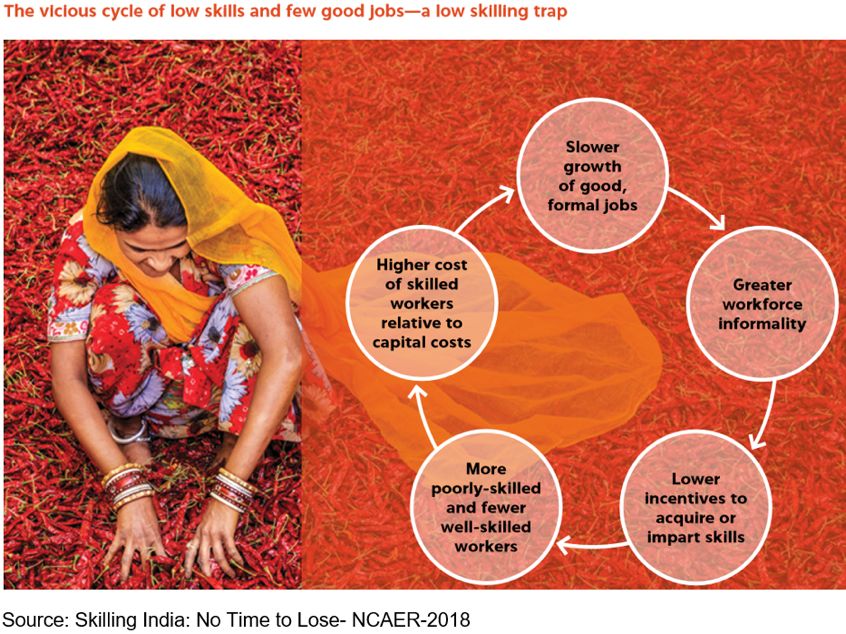

The above framework can be used by policymakers and implementers to create effective skilling systems to lift Indian workers out of a low skills quagmire towards lifetime employability.

The first step in breaking the cycle of low skills-not enough good jobs is to impart demand-driven skills. Market intelligence plays a pivotal role here to unravel hurdles in creating suitable jobs and skilling individuals appropriately:

- Are linkages between industry and education/training systems strong?

- Is there a market for the skills being imparted?

- Are there adequate opportunities for on-the-job-training such as apprenticeships?

- How to boost Recognition of Prior Learning- especially for those from India’s heaving informal sector. 92% of the current workforce is engaged in the unorganised sector.

The widespread mismatch between the supply and demand side of skills acquisition indisputably stems from inherent weaknesses in India’s education system. Without a proper integration of TVET (technical and vocational education and training) with mainstream education, Indian youth will continue to be victims of a huge disservice meted out by an archaic, out-of-touch pedagogy.

What’s Wrong with the World’s Largest Schooling System?

India’s education and vocational skilling ecosystem in vast. Yet its recipients often fall short of the market test of employability.

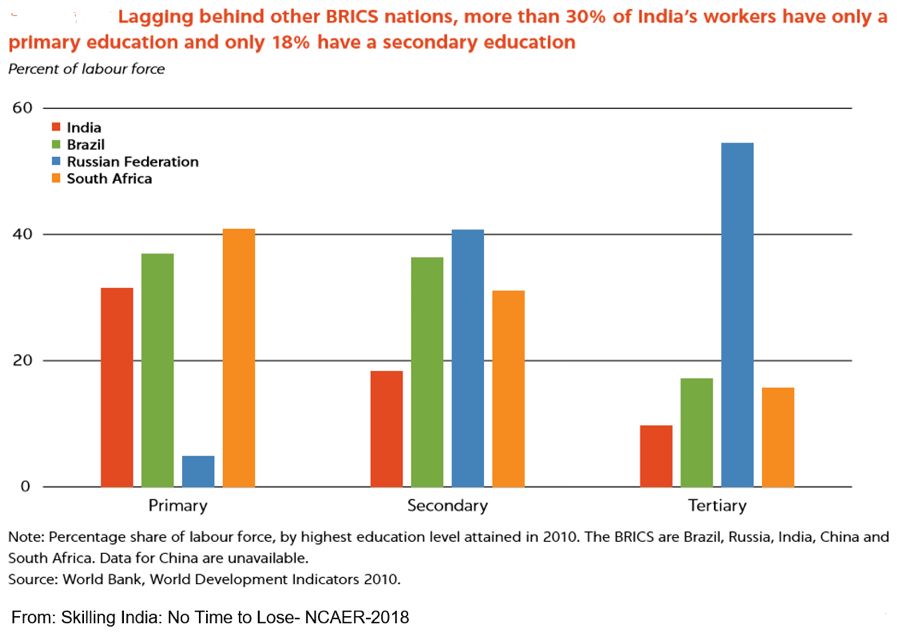

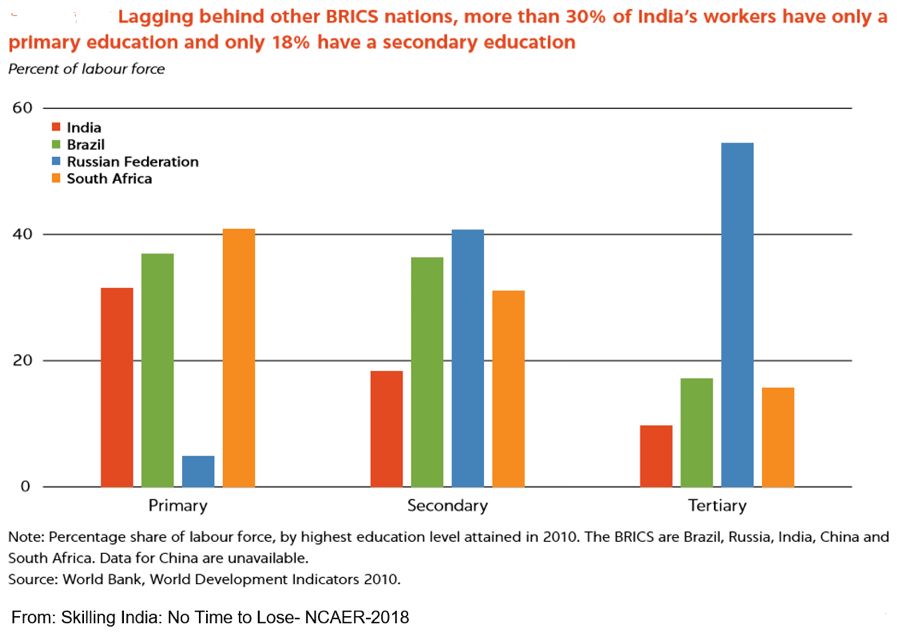

Indian workers lag far behind their BRICS counterparts in literacy. By the time youth reach secondary and higher schooling levels the drop-out rate peaks.

Where do these disenfranchised youths go? And why is the state of education so poor to begin with?

The report emphasises an overhaul is required- content and practical learning must match current and future workplace demand not only in technical and vocational skills but also in soft skills such as social and communication skills, critical thinking, problem solving etc. A combination of all such skills are of increasing importance to Indian employers.

To make vocational education more accessible, we recommend lowering the entry-point of vocational streams below the current Grade 9 level. This will massively benefit youth with a choice to acquire hands-on skills and get on the path to becoming skilled tradespersons even before they leave school. This has got to be better than exiting the schooling system with no education and no skills- which a vast majority of them do today.

Apprenticeships

Apprenticeships and other forms of on-the-job training make skills acquisition demand driven. How?

As aptly put by Joint Secretary MSDE, Rajesh Aggarwal, at a recent NETAP-IAF event, “Employers will promote apprenticeships in an area where there is a need for people and scope for employment. And the whole supply chain matching takes place at the apprenticeship stage.”

However, India must embrace apprenticeships with much more fervour. Only .1-.2 % of our organised workforce is made up of apprentices as against 5% in Germany. The report attributes the lowest youth unemployment in Germany among EU countries to a compulsory three year part-time vocational education for youth outside of the schooling system. India needs an urgent ratcheting up of the learning-by-doing and learning-while-earning approaches to make apprenticeships a valued career path with high employable skills gained from a dual-model of theoretical knowledge and real world practical on-the-job training. The report further

enunciates that degrees and apprenticeships in India must work together- the former confirming formal knowledge acquisition, and the latter marking a candidate’s job readiness.

Data-Driven

Curricula and teaching practices must be evidence-based on learning outcomes and what works – which we believe is possible only on good data. The paucity of credible skilling data in India challenges the very purpose of the various skilling programs. How does one measure outcome in the absence of nothing to compare with? Ergo, we laude efforts such as the Stipend Primer by TeamLeaseServices which provides critical market intelligence on apprenticeships in India.

The NCAER report strongly advocates stepping up data-driven analyses on what skills are imparted with what success factor not only through the education system but also for the vast number of government skilling schemes. To this end, it recommends the establishment of a National Skills Research Division within the MSDE to study the impact of schemes on the three themes of acquiring, matching and anticipating skills. It goes on to emphasise that even with improved market signals and understanding of required skills, the problems do not recede if ultimately India’s education and vocational systems, the torchbearers of imparting skills, do not adapt and evolve to make themselves relevant.

Less in Not Adequate

The value of an overabundance of existing short-term skilling programs has been questioned by the report. Vocational training of 150–300 hours neither boosts youth employability nor meets industry needs- a hugely wasteful exercise. Instead, the recommendation is for a minimum duration of one-year vocational skilling programs, akin to the apprenticeship model. Short-term courses can be used in recognising and certifying prior learning.

Next Up

Matching and Adjusting Skills- the next component of the three-part framework.

Reference

[i] Main source: ‘Skilling India: No Time to Lose’- 2018- National Council of Applied Economic Research