World-over there has been a steadily growing interest in apprenticeships as a path to employment and increasing skills in youth.

Not surprising, given that around 73.3 million people aged 15-29 and a fifth of all young people in the European Union are unemployed and seeking work.

Youth unemployment and lack of skills are gnawing issues in India too, typically amplified for youth from socio-economic backward environments where they face barriers to education and training opportunities. This is or should be of particular concern to policy makers and enterprises as research has shown that early labour market experiences can have long term negative effects on an individual’s entire working life. Young people who are disconnected from work early in their careers have a particularly difficult time to establish stable future employment.

The G20 states “apprenticeships are a combination of on-the-job training and school-based education. In the G20 countries, there is not a single standardized model of apprenticeships, but rather multiple and varied approaches to offer young people a combination of training and work experience”.

Central to this is employer engagement at the local level to provide quality work-based experiences critical to the success of any national apprenticeship program. Local apprenticeship uptake supports regional development objectives and provides local employers with a pool of skilled workforce to thrive and foster job creation. Besides technical skills apprenticeships equip youth with job-ready soft skills like problem-solving, conflict management and entrepreneurship which are much more potently developed in workplaces than classrooms.

Read: What’s in it for businesses to engage with apprenticeships?

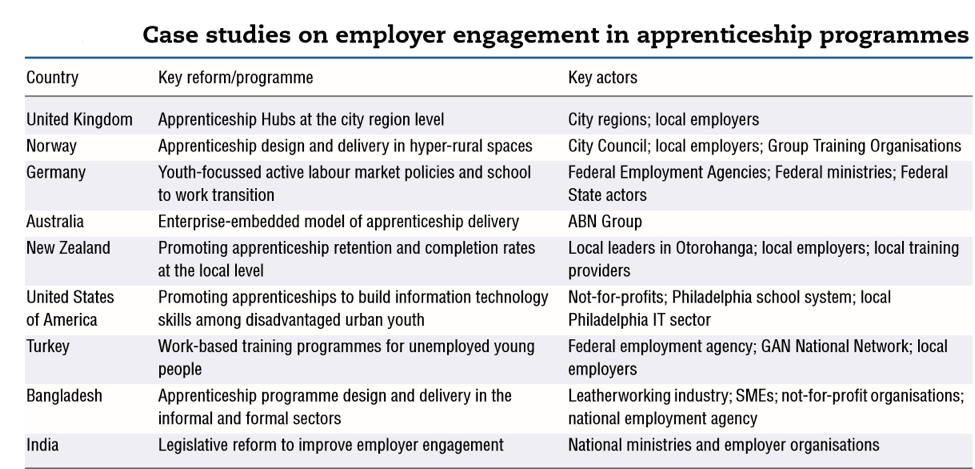

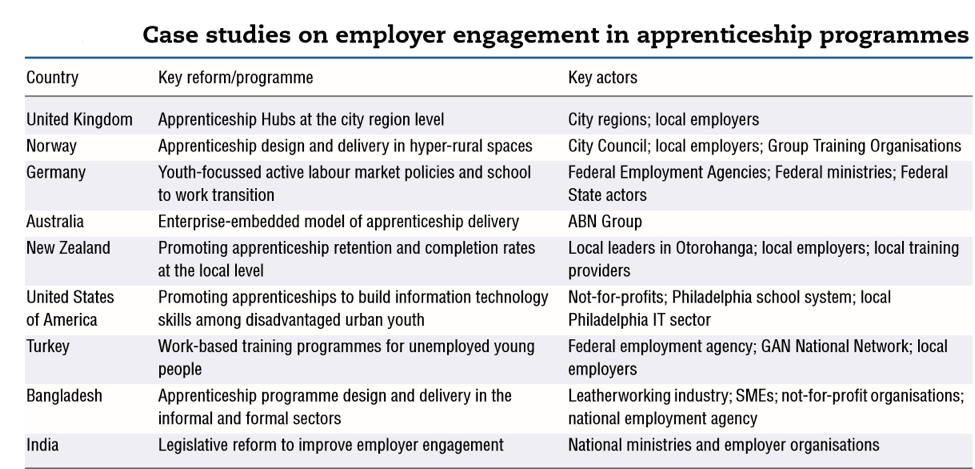

It is against this backdrop that we explore the report ‘Engaging Employers in Apprenticeship Opportunities-Making it Happen Locally’ (OECD/ILO). Employer engagement is examined through nine cross-country case studies, including India, with examples of local leadership from SMEs in championing business-education partnerships. The report aims to provide learnings to engaging employers in apprenticeship programmes in local markets for bottom-up economic development.

Dual System

An overarching finding is that a dual system of education is a hallmark of a mature apprenticeship system, such as in Germany, Austria, Norway, Denmark and Switzerland which enables employers to actively engage in training programmes.

Other Key Lessons and Recommendations

- Engaging employers is key to strengthen alignment between the supply and demand of skills. Employers are best placed to advise on curricula development at local training institutes in line with labour market needs which in turn increases the employability of youth at the local level.

- National apprenticeship systems ensconced in centralised policy need employers at local levels to translate wider skilling objectives and schemes into local reality. The success of national schemes depends on acceptance by employers and integration into the workplaces of local businesses.

- “Spaces” or networks for employers to provide guidance to local and regional governments in industry demand for skills is crucial to bridging skills-jobs mismatches.

- Particular assistance catered to SMEs is required through policy frameworks to enable them to be providers of apprenticeship places. This is to counter limited resource capabilities of SMEs through measures such as incentives, tax breaks and industry/sector networking platforms.

- Youth require customised support and guidance and enterprises are best placed to provide these.

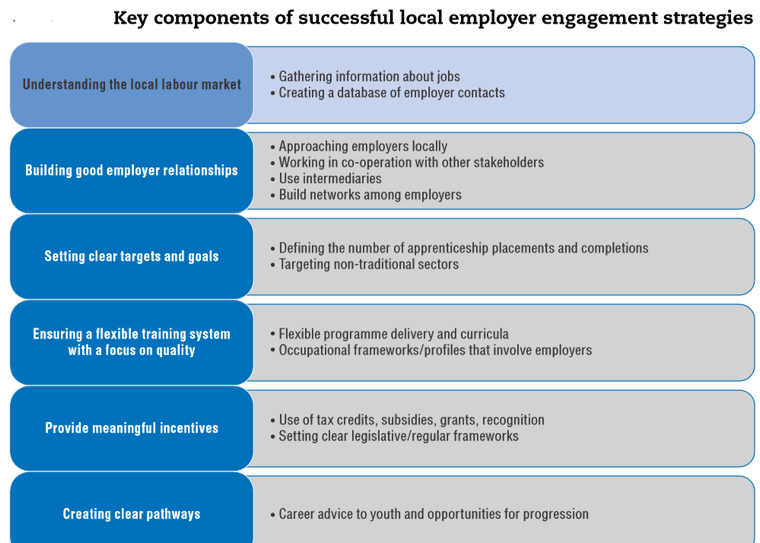

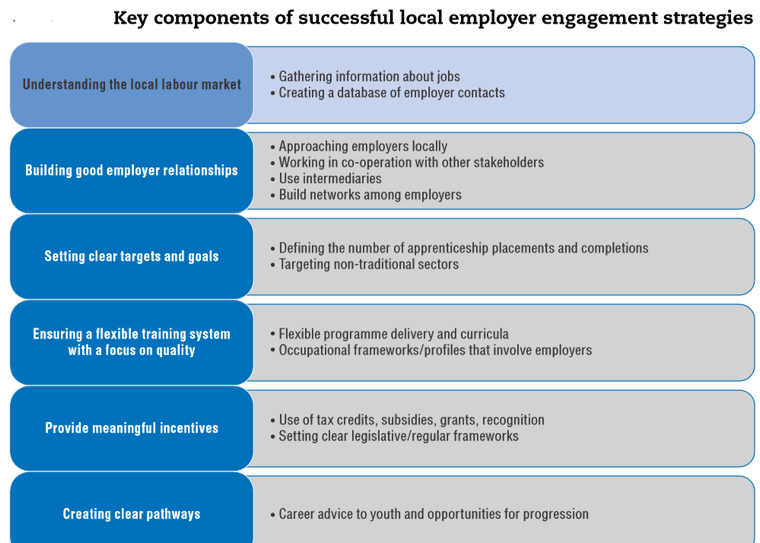

Below is a round-up of findings across the nine case studies on best practices to increase employer engagement at the local level in the design, development and delivery of apprenticeship programmes.

Barriers to Employer Engagement

Estimates show differences across countries on how much employers choose to become engaged in providing apprenticeship and training places; from below 1% in the United States, to 8% in England and 30% in Australia.

The reasons vary from onerous complex structures of institutions, unclear incentives in accessing government support, to receiving local advice for employers from government representatives. For instance, the English case study revealed a preference for speaking to a real person rather than navigating an impersonal national website.

What SMEs Require

SMEs make up 99.9% of the UK’s enterprises but less than 25% provide apprenticeship places. This still adds up to around 120,000 workplaces in the UK who employ apprentices. In contrast, only 24,000 Indian employers engage apprentices.

SMEs command a sizeable share of a country’s economy. Their low participation in the apprenticeship system stems from reasons of scalability, variable & seasonal demand, low utility perception, remote locations and low awareness. Hence specialised assistance goes a long way, especially for SMEs in developing countries, where an apprenticeship or skills training may be the only route for large swathes of informal workers to learn a trade.

There are urban-rural differences in the needs of SMEs too. Rural SMEs may face specific challenges of access to education and training services due to remote locations. Urban SMEs may require more support to link with other local businesses for training partnerships. This underlines the need for local government and policy bodies to be flexible and adaptive to local needs in programme design and regulation.

SMEs are also often faced with underdeveloped in-house human resource functions which are unable to participate in apprenticeship schemes. Hence localised support to HR personnel of SMEs can be a valuable service.

Customised Apprenticeship Placement Services for SMEs

In 2007 Germany introduced a new programme to boost placement of trainees in enterprises (PV). The aim was to enable SMEs, particularly in the craft and services sectors to get access to youth for dual vocational training. The premise was that SMEs traditionally face more barriers in attracting candidates without support from third parties compared to larger organisations. The PV programme funds agencies, typically non-profits or chambers of commerce/craft, who offer placement services. This works well as less than 5% of companies hire apprentices directly and the PV scheme offers a more personalised service to SMEs. The agencies work in close partnership with local enterprises to ensure a good skills match.

Collective Training Offices

These are set-ups in Australia and Norway that act as an intermediary between employers, apprentices and the government. They essentially take away from employers the bureaucratic and administrative hassles thus freeing up more employers to engage with the apprenticeship system.

In Norway, collective training offices draw up contracts with the government on behalf of SMEs. The legal obligation for off-the-job training is then dispersed among the collective training offices, who use economies of scale to provide a holistic training experience to apprentices.

Local Champions

An employer in the local building and construction trade in Western Australia saw skill shortages in the local labour market due to a shift in the workforce to the mining industry. The employer initiated a discussion committee which included representatives from the state government, industry associations and trade unions. This resulted in a rejig of the regional apprenticeship system to employ apprentices based on the Recognition of Prior Learning approach and the development of business specific competency-based learning frameworks. This provides valuable insight into how active participation from employers can serve local business needs.

Perception

Apprenticeship programmes are often challenged by perceptions of a ‘lesser education’, both by youth and their families. We have examined this in our post Are TVET and Apprenticeships a Second Class Education or a Game Changer?

Drumming up local success stories by employers and community leaders can lead to changing mindsets where skills are considered as valuable as traditional degrees. This is especially true in cases where youth feel misaligned from the formal education system. Apprenticeships then become a life-changing way out.

Apprenticeship Hubs

To encourage and draw in more engagement from SMEs the Leeds and Greater Manchester city regions of the UK have started local apprenticeship hubs. Each local hub is free to run their own activities in line with local business needs. The result was a surge in vacancies due to employer participation allowing the hubs to shift focus on onboarding more youth into apprenticeships.

Employer Led Initiatives

Akin to India, Bangladesh has a large informal workforce which plays a prominent role in the labour market. The leather sector in Bangladesh is a high export growth area. The Centre of Excellence for Leather Skill Bangladesh Ltd (COEL) was started as a non-profit and is employer led by 25 enterprises. COEL estimates a demand for around 60,000 skilled workers with a further shortage of managers and entrepreneurs.

The COEL initiative has met with considerable success strongly backed by local employers with support from external partners and donors. Almost 100% of trainees get placed after a combination of 3 months classroom-based training at the COEL training facility and 9 months of workplace training in factories. The COEL is an example of local leadership from the business community in demand-driven skills training and job creation.

PPP Model

In India, an example of a public-private working model is the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC). One of its main focus is to engage the private sector in awareness and capacity building, loan financing, the creation and operations of Sector Skill Councils, and overseeing skill assessments to standardise certification. Furthermore, the NSDC also looks into the area of corporate social responsibility to engage employers.

Conclusion

Local stakeholders such as enterprises can make the difference between success and failure of apprenticeship programmes. Hence grassroots participation becomes a precondition to building a high quality apprenticeship system supported by local governments, agencies and community partners.

Source: Engaging Employers in Apprenticeship Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris, OECD/ILO (2017)