TVET (Technical and Vocational Education and Training) in India is often marred by inefficiencies owing to the problem of too many cooks – 17 departments under various ministries tasked with varying degrees of responsibility for delivering vocational training and skills development under a plethora of governmental schemes. In this concluding section of our deconstruction of the UNESCO-ILO report ‘Taking A Whole of Government Approach to Skills Development’, we examine the TVET ministerial system in India.

The Blueprint

India does appear to have a strong foundation for vocational skill development with a clear governance framework. It enjoys a dedicated TVET ministry – the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) established in 2014, to improve communication and streamline coordination between myriad ministries. This report states, countries in which TVET is led by a dedicated government agency or is decentralised tend to witness an above-average performance.

The MSDE is guided by the National Skill Development Mission which was approved by the Union Cabinet in 2015. The Mission was developed to bring about harmonious working across sectors and States in vocational skills training activities. Also tied to the Mission is the government’s aspiration to ‘Skill India’.

The various entities functioning in the skills space under the MSDE are:

- The Directorate General of Training

- The National Council for Vocational Training

- The National Skills Development Agency

- The National Skills Development Council

Additionally, it has the support of the:

- The newly formed single regulator for skills training – the National Council for Vocational Education and Training – which replaced two earlier regulators. This move is expected to bring more cohesiveness in both inter-ministerial and private player efforts in the skill development space.

- The National Skill Development Corporation – a public-private partnership with an important mandate to bring industry representation to the table.

- The National Skills Qualification Framework (NSQF) – adopted in 2013, the NSQF provides a competency-based framework to standardise skills certification across job roles and sectors.

But how close are we to achieving the objectives of consolidation of inter-ministerial skilling efforts, accelerate decision making, establish consistency in skilling certification and standards, and most importantly making a real impact on skilling our millions on the required scale?

What Can Be Better

A few things, state experts. The National Skills Qualifications Committee (NSQC) is responsible for implementation of the NSQF but has played a lackluster coordination role so far. In the 12th Five Year Plan the notification on the NSQF stated, “it shall be mandatory for all/educational programmes/courses to be NSQF compliant and all training and educational institutions shall define eligibility criteria for admission to various courses in terms of NSQF levels.” However, a critique of the current situation is that the NSQC has neither been able to anchor the NSQF in the country’s education system nor achieve standardisation and national recognition of skills training and certification.

Problems in India are often presented on two extreme ends- too much or too little of something. The NSQC is led by secretaries of the government with little expertise on course design made up of National Occupation Standards (NOS)- specific tasks within job roles, and Qualification Packs (QPs)- competencies required to perform a task. As of 2017, there were almost 10,000 NOS and 2000 QPs. Whereas globally, the International Standard Classification of Occupations recognises only around 450 main occupations.

Moreover, to throw yet another acronym into the fray, the National Quality Assurance Framework (NQAF), essential for recognition of the qualifications in the NSQF, is yet to be endorsed by the NSQC.

Also read: Role of Quality Assurance in TVET

Another finding of this report, countries which vet their vocational skills training strategies, decision-making and actions on strong or above average availability of accurate labour market data reported higher graduation and employment rates under the TVET route.

Also read: Deconstructing the Apprenticeship Stipend Primer 2019 – Part I

In India, the dearth of reliable market information on sectors/occupations with skills shortages split into national/regional/local levels, anticipation of future trends, the efficaciousness of the various skilling programmes from the perspective of real outcome and not just enrollment numbers, have all posed serious constraints to demand-based skills training and employment generation.

Furthermore, as this report suggests, an opportunity for improvement in inter-ministerial coordination is for ministries and states to regularly integrate their own labour market information into the national LMIS and not operate in silos, a tendency pervasive today. A similar point taken up strongly by the Niti Aayog’s ‘Strategy for New India @ 75’ where it calls for enhancing skills and apprenticeships through a comprehensive LMIS to identify skill shortages and training needs.

In Conclusion

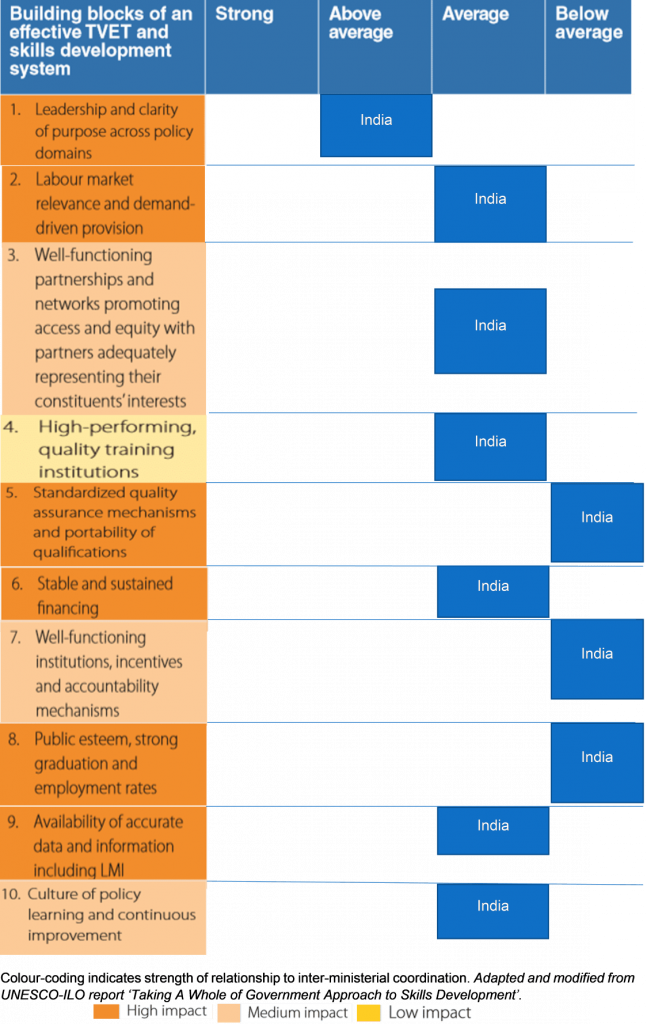

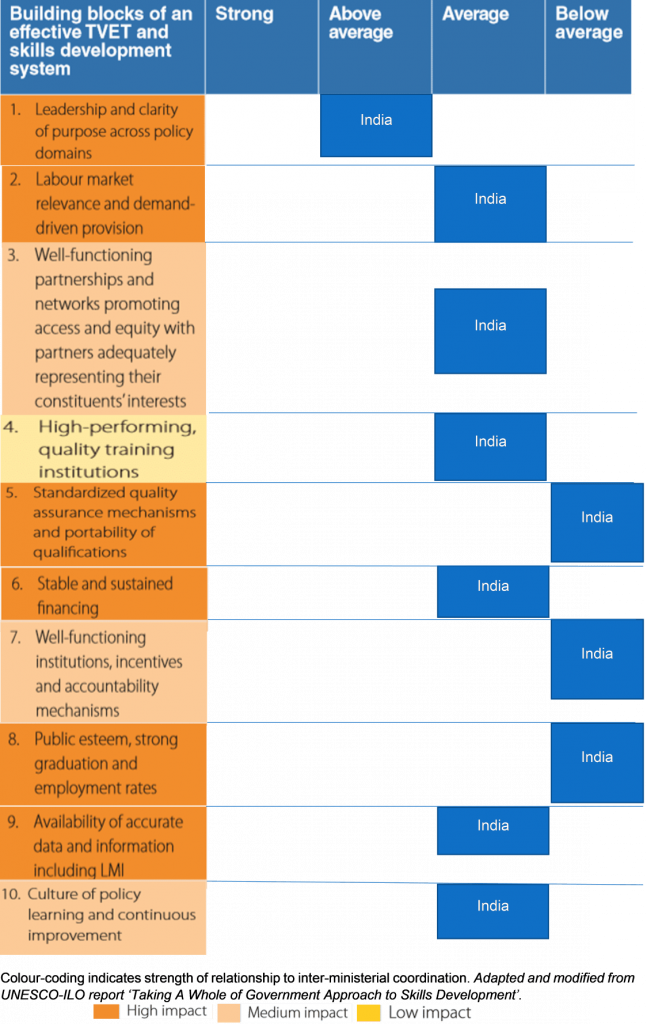

Having a dedicated TVET ministry in India (the MSDE) certainly helps. But how much has that improved inter-ministerial coordination, as well as in the ’10 building blocks’ of an effective TVET system? We still have quite a distance to go.