Quality assurance in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is an indisputable pillar of a robust apprenticeship and skills based ecosystem. However, quality assurance being an involved process requiring close thoughtful attention to every stage of the delivery mechanism tends to at times fall by the wayside in a rush to gets things off the ground.

The employability of Industrial Training Institute (ITI) pass-outs is a case in point; the latest India Skills Report[i] revealed a dramatic drop of 30% between 2017-2018. Although the reasons have not been specified this is highly concerning given that ITIs are a major pipeline for technical and vocational skills training in India. It is fair to assume that quality of the curricula, trainers, mode of teaching, quality of infrastructure, processes for assessment and certification, and alignment of skills training to actual demand could be contributing in varying measures to low employability, and it all comes down to quality assurance.

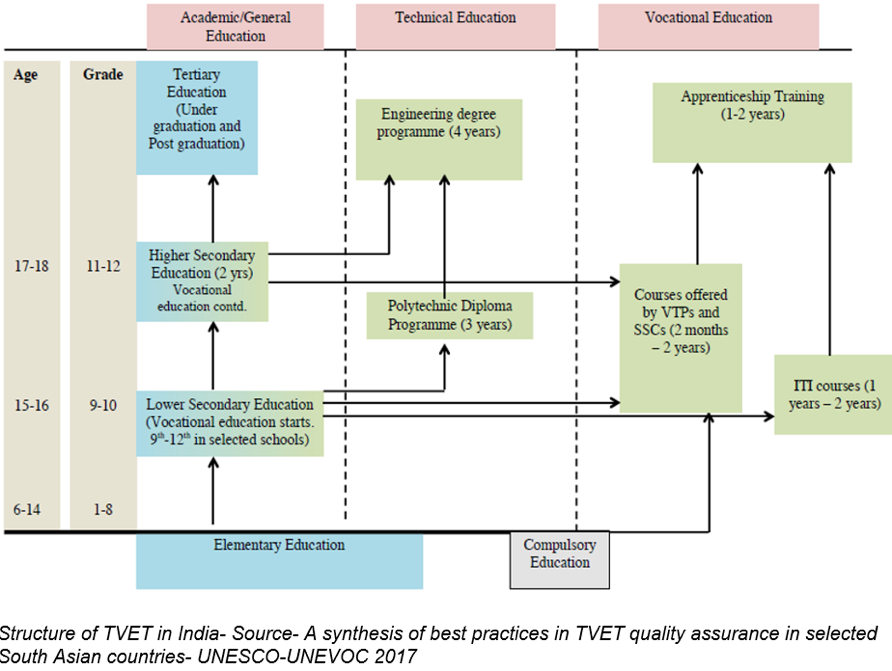

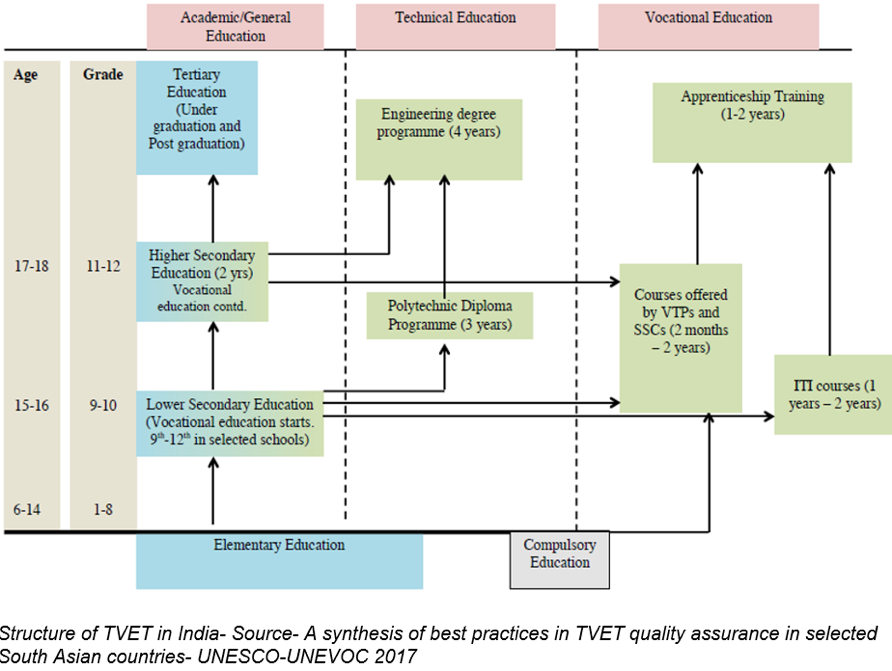

TVET Structure

Quality assurance in apprenticeships and TVET is fundamental to every stage of the structure of TVET education in India if learners are to acquire the knowledge, skills, and competencies needed for jobs and sustainable careers. Therefore, all relevant national and international standards of quality assurance and quality control need to be applied to each vertical and horizontal pathway of TVET and this can be achieved by adopting quality assurance management mechanisms to ensure consistent quality of training.

We look at two critical components of quality assurance in Indian TVET.

NSQF

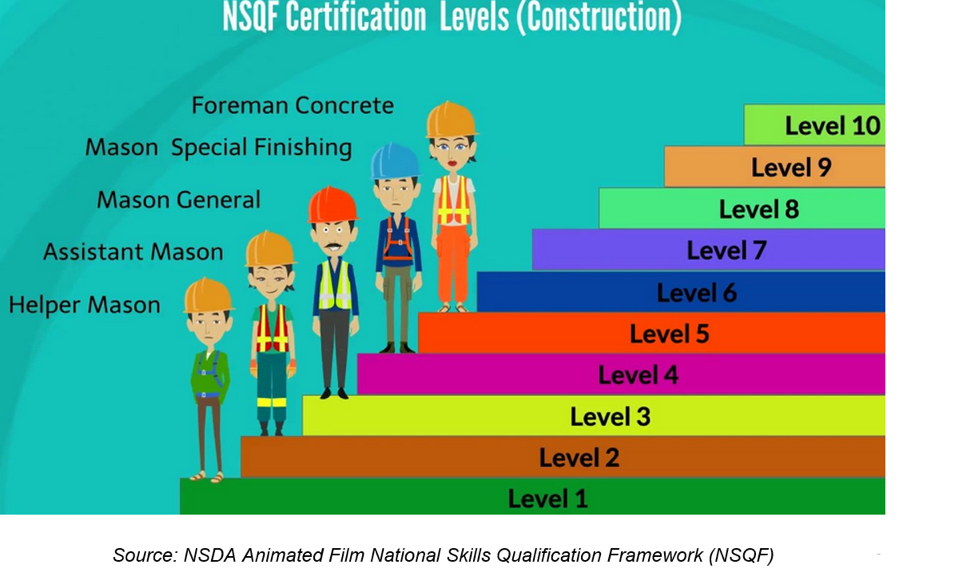

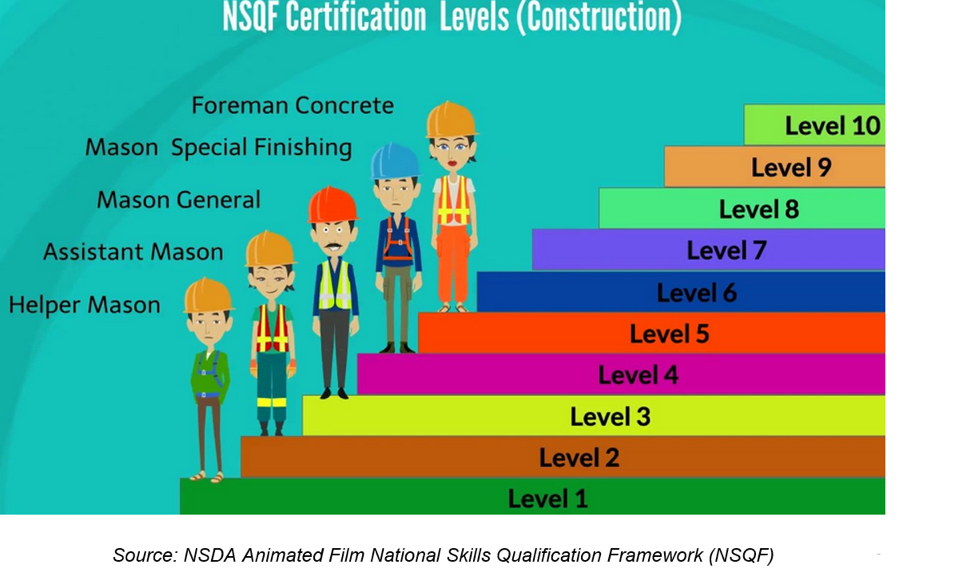

At the heart of quality assurance in TVET lies qualification frameworks to bring coherence to qualifications systems. The National Skills Qualification Framework (NSQF) was thus birthed in 2013 to place qualifications in skills based training within a classification system to be recognised by individuals, employers and educational/training institutes. A key role of the NSQF was also to harmonise qualifications issued by different bodies in the skilling landscape. A competency-based framework, the NSQF structures all skills based qualifications in a series of levels of knowledge, skills and aptitude, graded from one to ten measured in terms of learning outcomes, which the learner must acquire whether through formal or informal learning.

The NSQF is implemented through the National Skills Qualifications Committee (NSQC) which develops national occupational standards (NOSs)- specific tasks within job roles, and qualification packs (QPs)-the competencies needed to perform a job role.

Some of the key objectives of the NSQF as a core instrument to strengthen regulation and quality of education and training is to:[ii]

- Harmonise the fragmentation in vocational education and training systems

- Develop nationally recognised qualification sets for each level of the competency based graded system

- Build mobility for learners through progression pathways, with access to NSQF-compliant qualifications in different education and training sectors, and between those sectors and the labour market

- Give due recognition to prior learning and experience

- Allow the award and transfer of credits within general and vocational education systems

Role of the NSDA

The National Skills Development Agency (NSDA), an autonomous body under the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) secures the NSQF and related quality assurance mechanisms through the National Quality Assurance Framework (NQAF)- a benchmark to which all entities offering NSQF-compliant qualifications must adhere to.[iii] In particular, the NQAF stresses on improving outcomes of TVET and general education to boost employability. Quality in reference to the NQAF includes processes and outcomes which will closely align programme delivery, assessment and qualifications of learners to current and future industry demand for skills.ii

The NSDA also acts as a nodal agency for state skills development programmes, and streamlines operations of various skill development central ministries and departments, state governments and the National Skill Development Corporation.ii

Problems with QA in TVET in India

The following factors contribute to a nationwide malaise in quality of TVET education:[iv]

- Too many regulations, certifications

- Low coordination between government agencies and regulatory bodies

- Lack of autonomy

- Skills demand and supply mismatch

- Low academia-industry linkage

- Outdated and misaligned curricula

- Lack of qualified teachers

- Poor training infrastructure

Other criticisms point to poor design of the NSQF by those who have neither knowledge of pedagogy nor industry expertise which has resulted in 10,000 NOSs and 2000 QPs whereas globally only around 450 main occupations are recognised by the International Standard Classification of Occupations. “There cannot be thousands of standards (compressed into 2,000 qualification packs/job roles), and “delivered” to trainees in a matter of a few months. This is not what the NSQF had recommended,” says Santosh Mehrotra, Professor, Centre for Labour, JNU, and lead author of the NSQF.[v]

There also hangs a question mark on how well training providers understand the NSQF. And the matter of 17 different ministries besides the MSDE which oversee skills training– with little synchronisation among them.[vi] The NSQF standards hence stand on shaky grounds given the garbled workings of too many cooks stirring skill development schemes in India.

Ashutosh Pratap- policy advisor and strategist, and Santosh Mehrotra speak of boosting quality control across what they refer to as the five pillars of TVET in India:[vii]

- Vocational education in schools and institutes of higher education

- Vocational education by NSDC’s private vocational training partners

- Public and private ITIs

- In-house or on the job training by private companies

- Skill development schemes of the Centre’s multitude of ministries.

“While introducing greater coordination, we should work for standards that are not only nationally acceptable but also internationally comparable,” they say.

Yet another issue with the current TEVT system that adds to its inadequacies is whether it is in reality agile enough to allow seamless awarding of credit transfers from skills training to general education and vice versa, and whether there is flexibility for learners to use various entry/exit points when they move through both competency-based and traditional schooling pathways.

Quality Assurance Pay-off

The good intent behind the NSQF in enhancing the quality of skills delivery is obvious. The shift from learning input to learning outcomes in training delivery is a crucial step towards quality assurance. The NSQF and its allied quality assurance mechanisms lie at the heart of a nationwide hankering for skills transformation as a way to continuous improvements in both the quality of vocational education and how it relates to actual demand for jobs and skills.

Ironing out current issues in the NSQF and the manner in which it has been implemented will ultimately impact the quality of training delivery by the main geneses of training in the country- the ITIs, Advanced Training institutes, Regional Vocational Training Institutes and other central training institutes. And these in turn will leave their mark on the quality of job seekers and the responsiveness of the country’s TVET mechanism to trends and forces of the labour market.

References

[i] India Skills Report 2019- All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), Association of Indian Universities (AIU) along with Wheebox, PeopleStrong and Confederation of Indian Industry (CII)

[ii] A synthesis of best practices in TVET quality assurance in selected South Asian countries- UNESCO-UNEVOC, Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC) Sri Lanka, 2017

[iii] National Skill Development Agency website, as of 4/3/19

[iv] Challenges of Vocational Education System in India. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 2015

[v] ‘Skill India’ urgently needs reforms, Santosh Mehrotra, 6 April 2018, The Hindu

[vi] India’s skilling challenge: Lessons from UK, Germany’s vocational training models, June 4, 2018, Observer Research Foundation

[vii] Skill India Now Has a Single Regulator. Will It Succeed Where Other Bodies Have Failed? Oct 18, 2018, The Wire