Even with rising education levels many countries continue to grapple with a dual employment problem of how to skill youth and how to ensure those skills match industry demand for jobs. The jobs-skills mismatch has turned the spotlight on governments adapting their education and training systems to cope with changing market forces. Enterprises too find themselves on the back foot as they try to keep pace but face severe skill shortages among youth.

Context

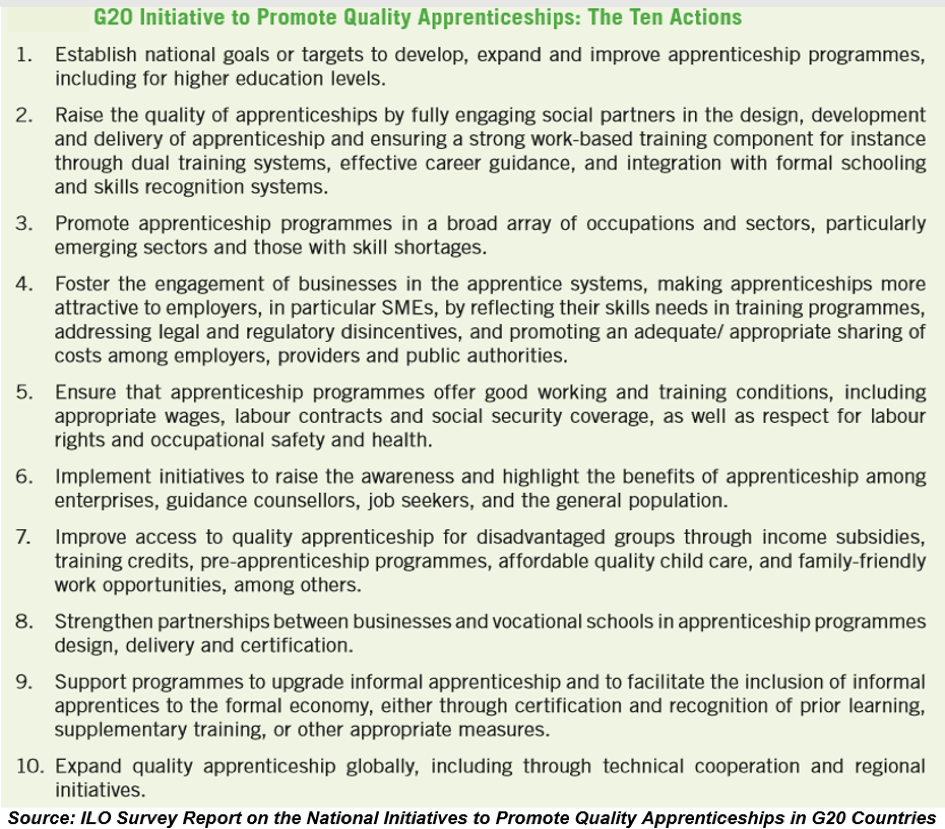

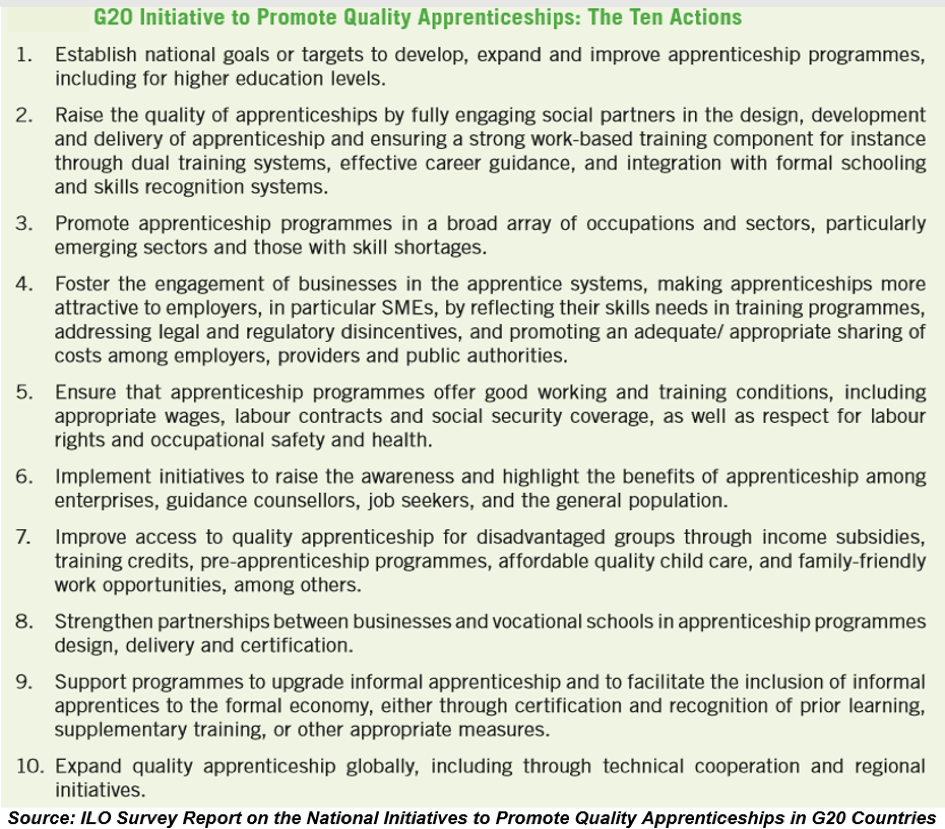

This is the sentiment upon which the ILO in 2017, supported by the JPMorgan Chase Foundation, launched the ‘Skills that Work Project: Improving the Employability of Low and Middle-Skilled Workers’. The project advocates ‘quality apprenticeships’ as a critical pathway to equip youth with industry relevant skills through real world exposure to work thereby enabling a smoother transition from education to employment. The G20, L20 and B20 (business and trade union organisations of G20 countries) have committed to the Declaration of the G20 Initiative to Promote Quality Apprenticeship which states:

“Given the importance of apprenticeship for improving the skills of our workforce, we agree to increase the number, quality, and diversity of apprenticeship through the actions outlined in the G20 initiative to Promote Quality Apprenticeship (Annex 3) based on national circumstances. We recognize that quality apprenticeship is based on the full engagement of social partners, businesses and workers. We encourage B20 and L20 to follow up their previous joint commitments and implement this initiative”

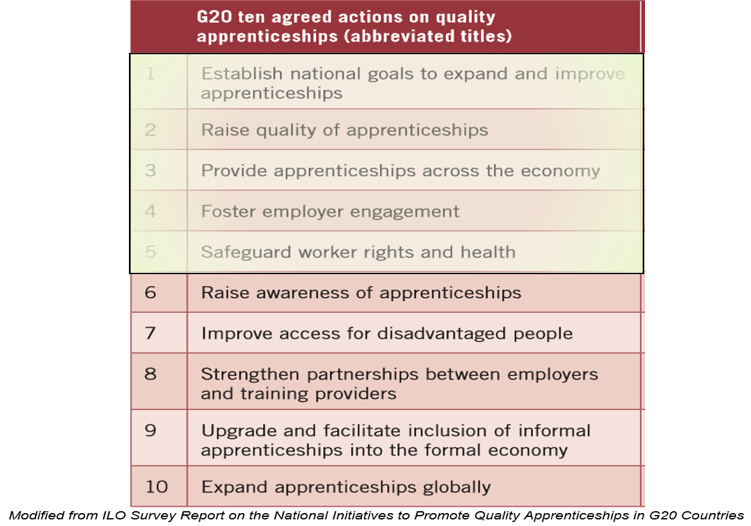

The Initiative consists of Ten Actions to boost the quality, quantity, and diversity of apprenticeships.

We discuss key findings of the ‘ILO Survey Report on National Initiatives to Promote Quality Apprenticeships in G20 Countries’[i] which spawned from the Skills that Work Project.

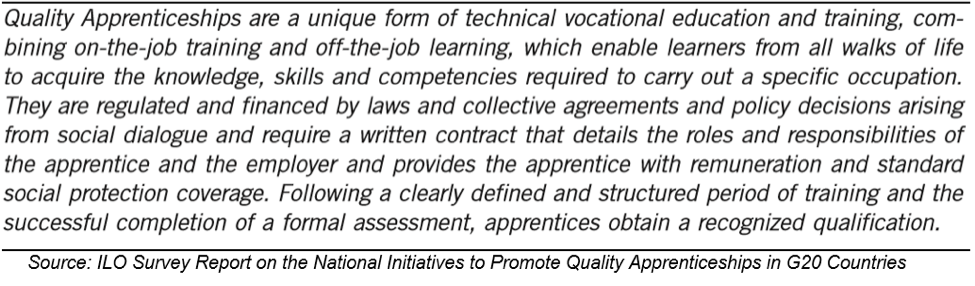

This ILO survey describes quality apprenticeships as:

Survey Objectives:

- To pool knowledge and map responses on national initiatives promoting quality apprenticeships against the Ten agreed Actions

- To make the data available for stakeholders

- To identify a baseline to track future progress of the G20 Initiative

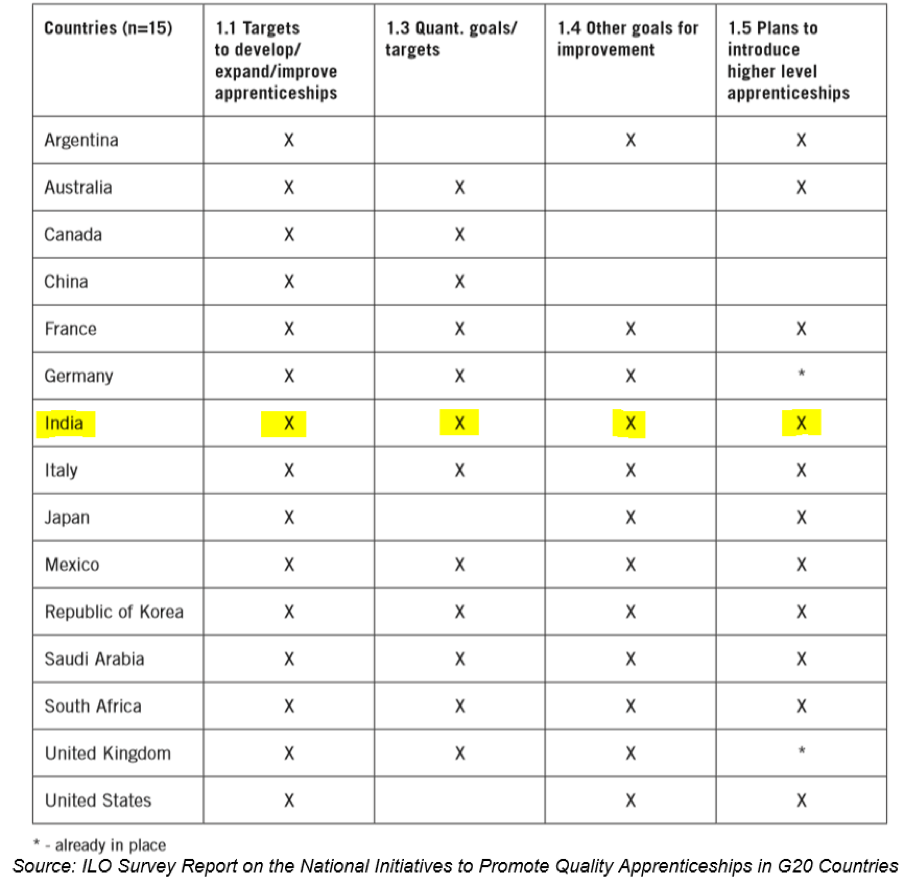

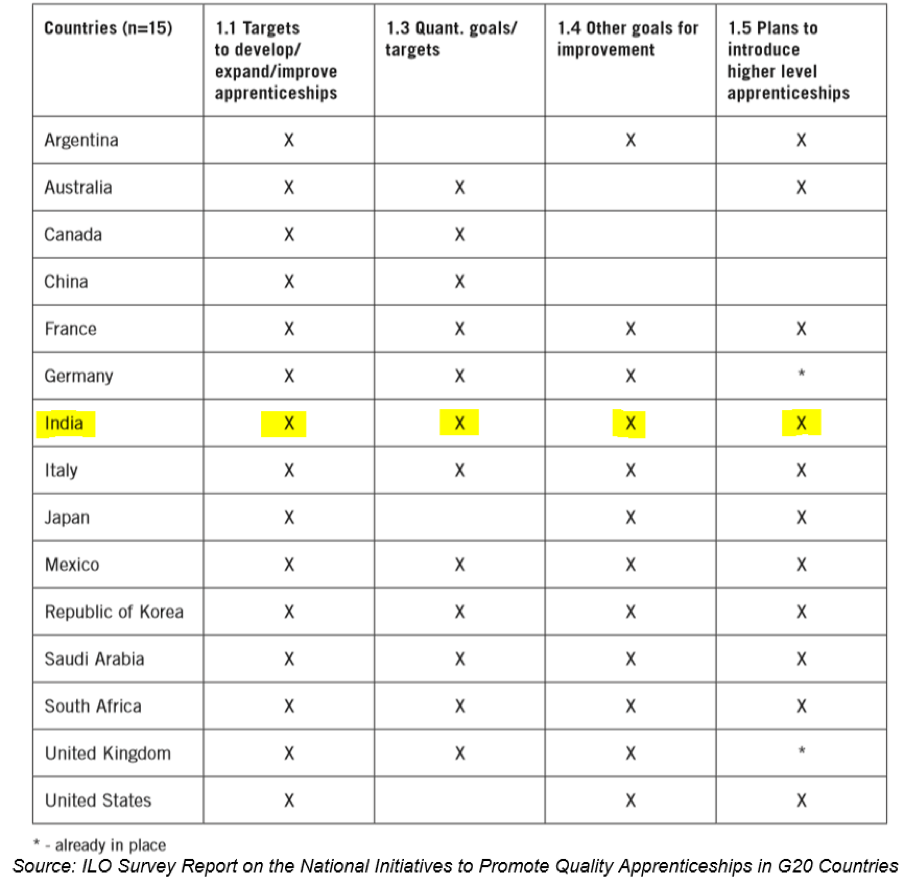

In Part I, we look at key findings and good practice on the first 5 of the 10 Action Points, from a survey of 15 influential governments of the G20. From India, responses were provided by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE). We delve specifically into findings from the Indian context.

- Establishing national goals to expand and improve apprenticeships

All countries who responded to the survey are actively engaged in boosting apprenticeship opportunities including the quality of skills acquired through apprenticeships. National targets have been set to promote quality apprenticeships with a majority of countries with plans to integrate apprenticeships with higher education, if not already done.

As we know, India’s goalpost to place 50 lakh youth in apprenticeships by 2020 was promulgated by the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) launched in 2016 to infuse new energy into apprenticeships as a win-win model for both industry and youth towards building a large skills-based workforce. However, as of January 2017, a mere 1.43 lakh youth had registered under the NAPS[ii] and at best there are 3 lakh apprentices in the country under various public and private models. India has its work cut out to boost its apprenticeship numbers. Of the 71 million enterprises, a paltry 50,000 of them engage with apprenticeships.

Coming back to the survey, in response to a question on non-quantitative goals to strengthen apprenticeships, the MSDE cited revamping the curricula for all apprenticeship courses with 63 of 258 completed at the time of the survey. We feel this is imperative, and needs action with much more gusto given the severe jobs-skills mismatch where it is estimated that a whopping 65-75% of youth entering the Indian workforce are either not job ready or are unemployable.

2. Raising the quality of apprenticeships

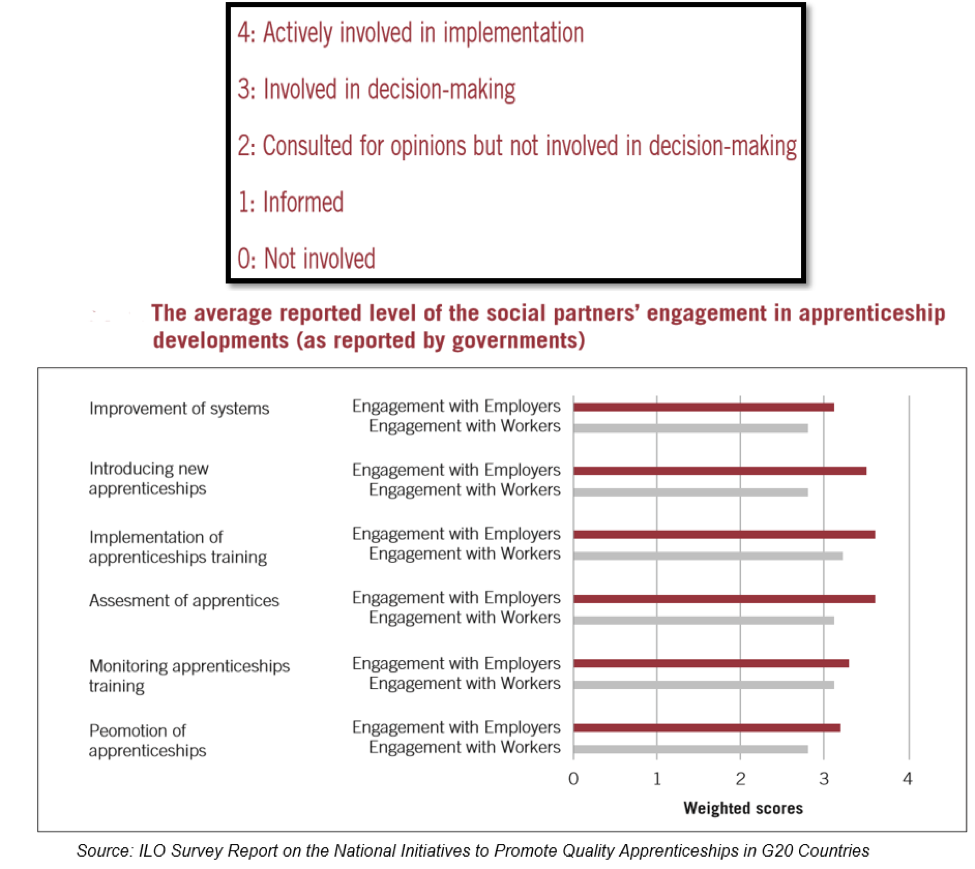

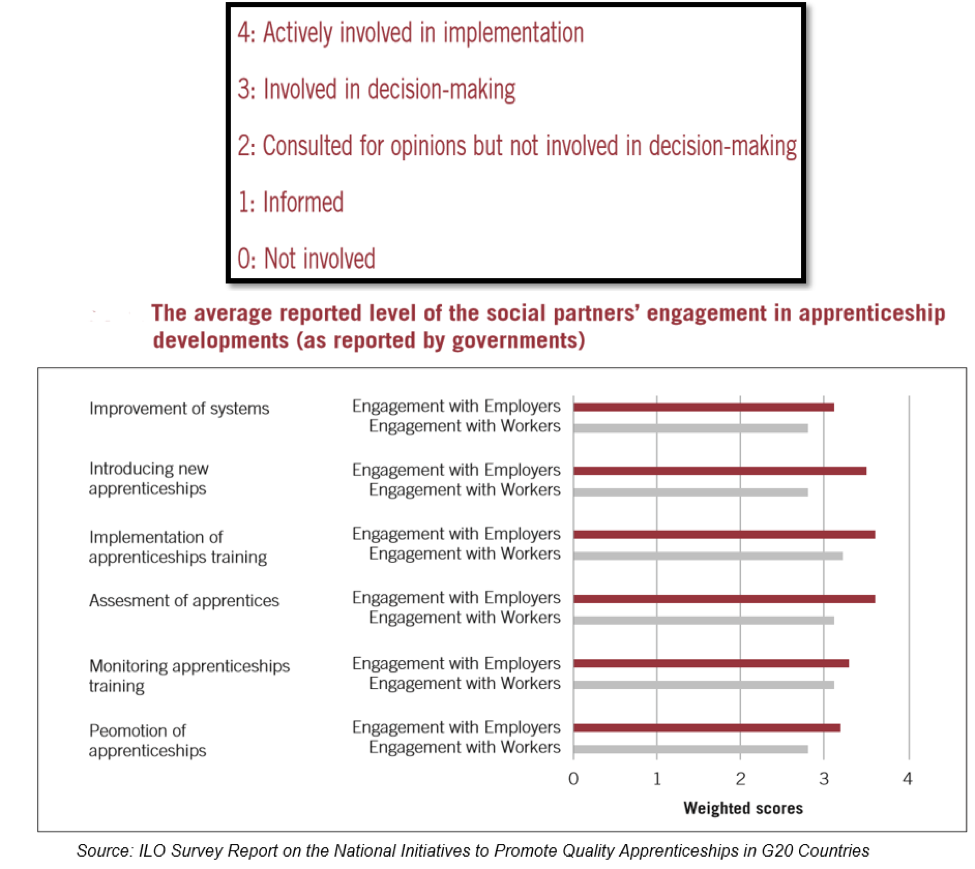

The survey found that a majority of governments seek to strengthen the involvement of social partners (workers’ and employers’ organisations) in recognition of their vital role in the design and delivery of apprenticeship training.

In the first component of Action 2, using a 5-point scale, responses were gathered for 6 different activities and how involved social partners were.

The second component of Action 2 asked about specific initiatives to improve the quality of workplace training in apprenticeships. The report does not specify if India responded to this question. Germany is highlighted as a front-runner in starting multiple targeted initiatives to enhance the quality of on-the-job training in apprenticeships.

The third component of Action 2 was split into three questions:

- The MSDE did not respond to questions pertaining to career guidance through employment services and online portals. It gave a response in the positive about career counseling by staff in TVET schools and centres.

- No response was registered for the MSDE on the availability of part-time apprenticeships as part of upper secondary schooling. To the best of our knowledge such a provision does not exist in the current Indian schooling system. Australia on the other hand stands out as a country with a high level of school-based part-time apprenticeship opportunities.

- In response to apprenticeships being part of the formal education system, the MSDE responded ‘yes’ to certification of apprenticeship being an educational credential but did not respond to an apprenticeship certification being a stand-alone formal credential or a combination of both. This points to further work needed to bring national recognition to apprenticeships by integrating apprenticeships with formal schooling.

3. Promoting apprenticeship programmes in a broad range of occupations and sectors

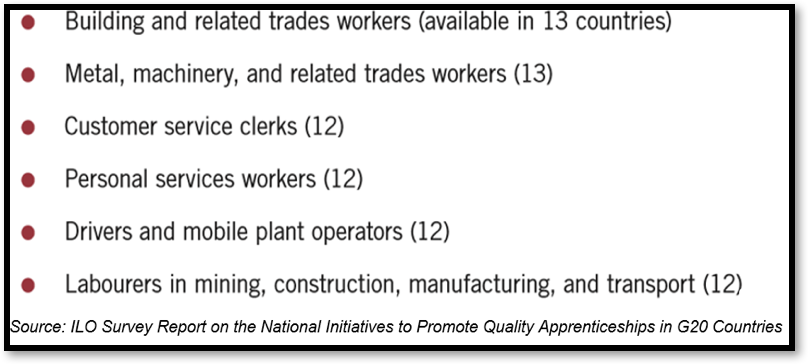

There is vast variance in occupational coverage of apprenticeships among countries. Some job roles such as sales exectuives and machine operators are more apprenticeship-based than others. Most countries cited intention to expand the reach of apprenticeships, especially those facing skill shortages. Some governments are also using apprenticeships to address new job roles in the face of Industry 4.0.

The top six occupations were found to be:

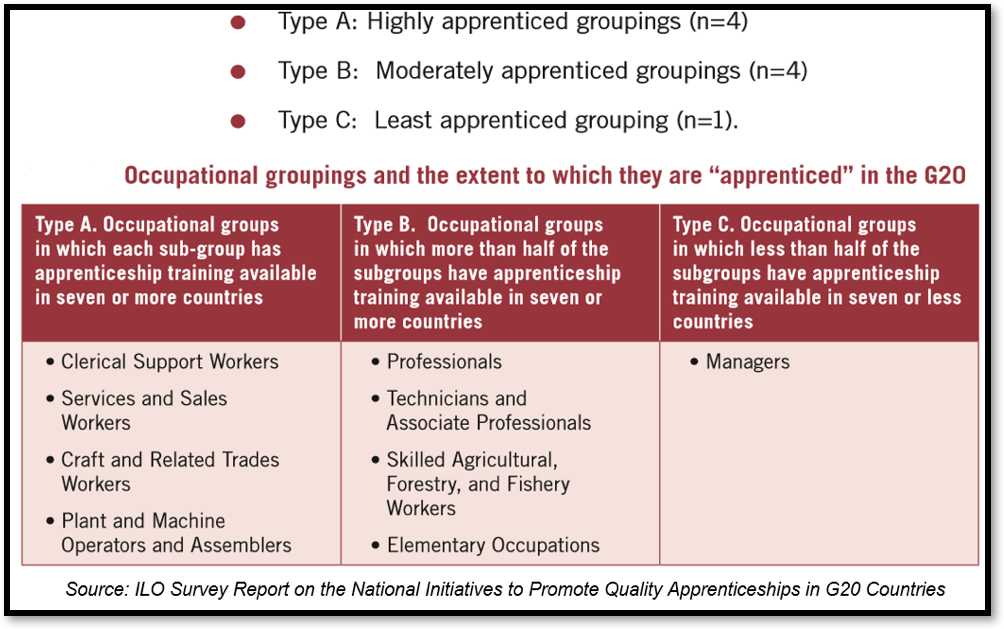

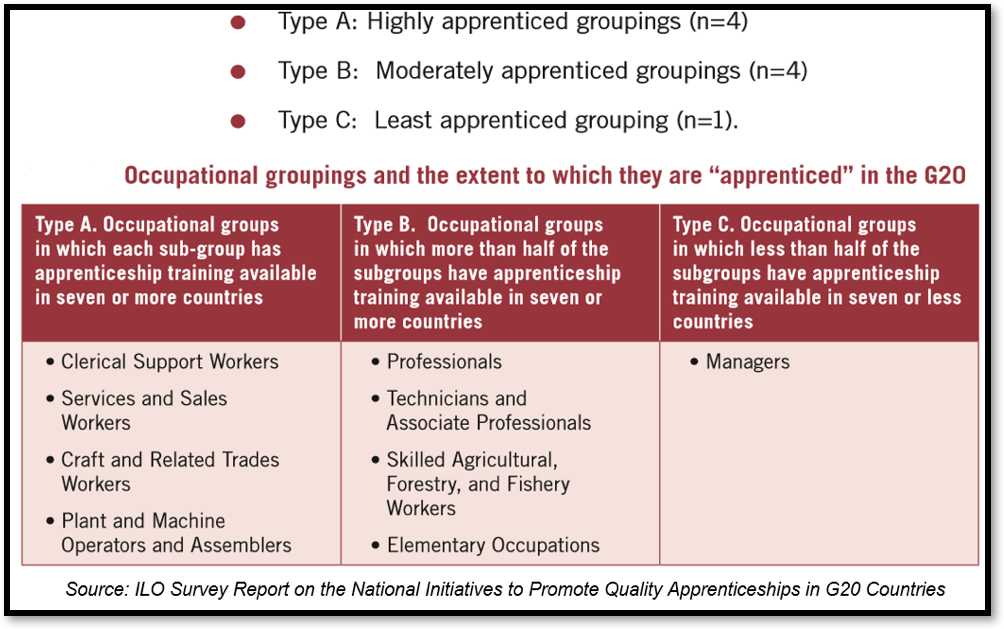

These are further split into three occupational groupings:

To the questions on expanding occupations for apprenticeships and promoting apprenticeships to address skill shortages, the MSDE answered ‘yes’ to both.

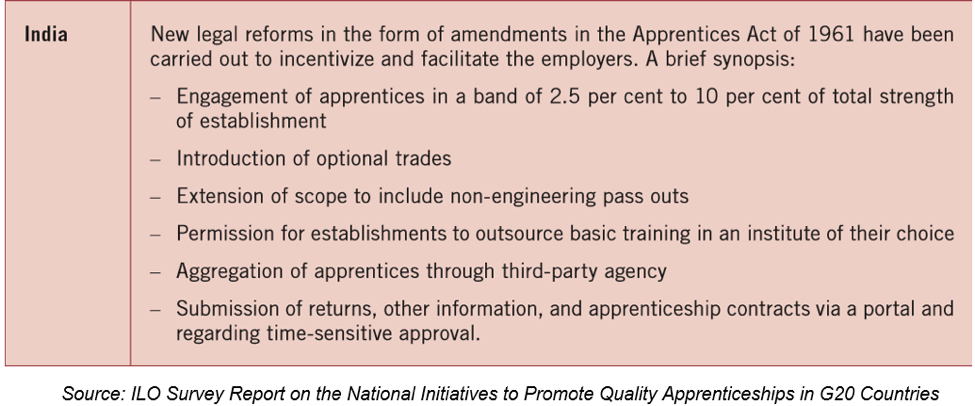

As we have noted in other articles, a key amendment to the Apprentice Act (1961) in 2014 was the tabling of a new category called ‘optional trades’- employer led and demand based, shifting flexibility to employers to design and customise apprenticeship training in any trade or occupation to suit their business needs.

4. Fostering the engagement of businesses in the apprenticeship systems

This is to bring SMEs into the fold of apprenticeships given their economic importance. To the question on how countries fostered the engagement of SMEs in apprenticeships, the MSDE cited the NAPS and its financial incentives for employers, and the role of State Apprenticeship Advisors in hand-holding employers through the apprenticeship process.

However, we feel a lot more can be done to encourage and engage SMEs whose staffing needs and HR processes typically vary from larger firms given their size and resource constraints. The Fifth Economic Census estimates there are 20,62,124 MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) in the country employing 6 or more staff. This is an exciting untapped potential; if each establishment engages even one apprentice, the MSME sector alone can generate 20 lakh apprentices.[iii]

Back to the survey, only two countries- India and the U.K reported specific mechanisms to identify SME skilling needs. The MSDE stated the Industry Apprenticeship Initiative (IAI) to identify and communicate SME skill needs. However, our own search has not revealed any more information on the IAI.

To the question of legal or regulatory reforms, aimed at incentivizing apprenticeships in SMEs, the MSDE pointed to industry-friendly changes to the Apprentice Act in 2014.

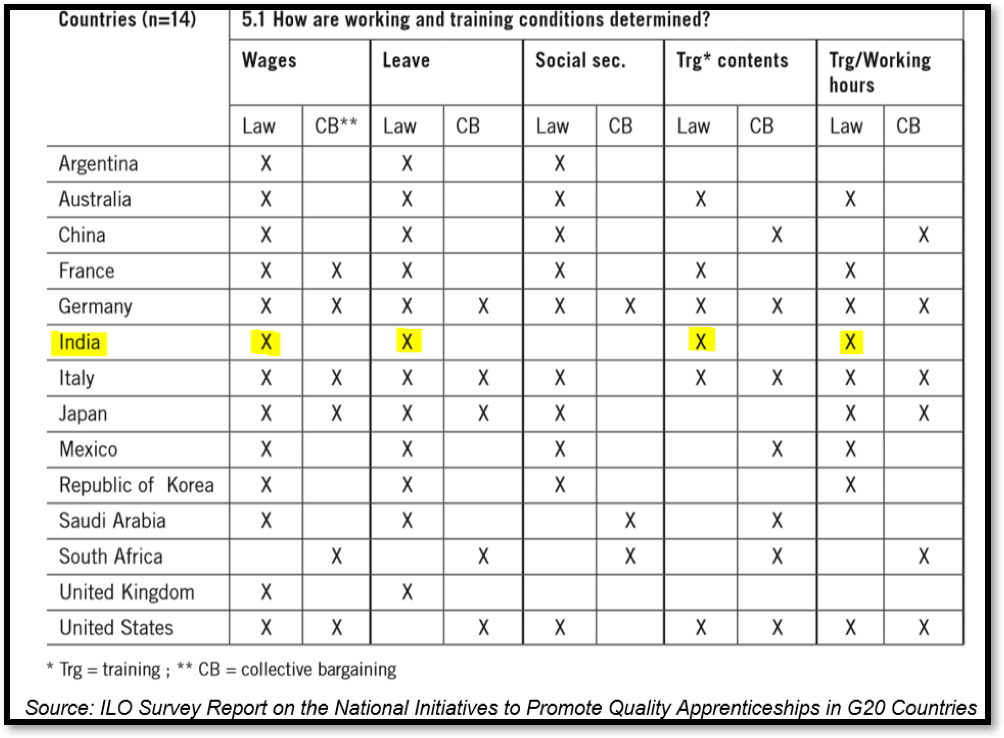

5. Ensuring good working and training conditions

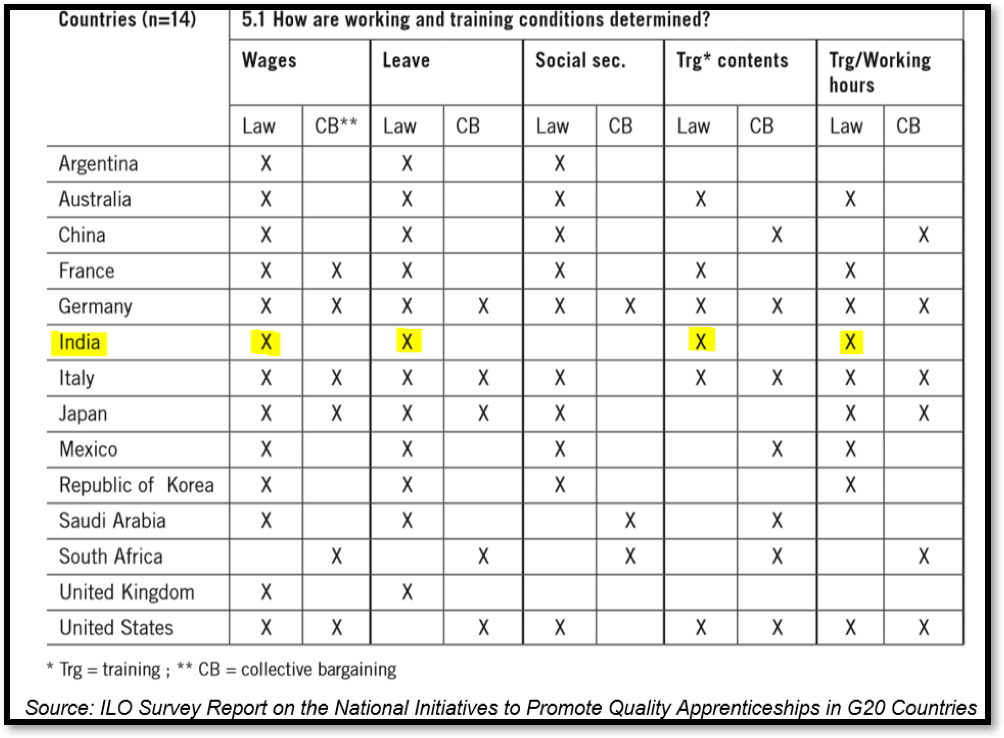

Large differences exist in the way apprentices’ working and training conditions are structured. In the absence of specific provisions for apprentices, social security benefits seem to be a measure of whether apprentices are considered regular employees or not, and what is determined directly between employers and workers.

Overall, it was found that countries tend to have legal provisions for the employment of apprentices rather than for the actual training delivered. We feel this is definitely an area that calls for improvement as the legal premises under which training takes place will go the distance to ensure consistency and quality of training.

Stay Tuned

In Part II we look at key findings and good practice on the remaining 5 Action Points.

References

[i] Main reference- ILO Survey Report on the National Initiatives to Promote Quality Apprenticeships in G20 Countries, ILO- JPMorgan Chase Foundation, 2018

[ii] National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme, Special Service and Features,

27-January, 2017 15:19 IST, Press Information Bureau, Government of India

[iii] Implementation Guidelines for Third Party Agencies Under the Apprentices Act 1961- MSDE